At this time, New York Times reporter Taylor Lorenz has currently had to lock her profile because of endless, disgraceful harassment from men in venture focused around her coverage of venture capitalists on Clubhouse.

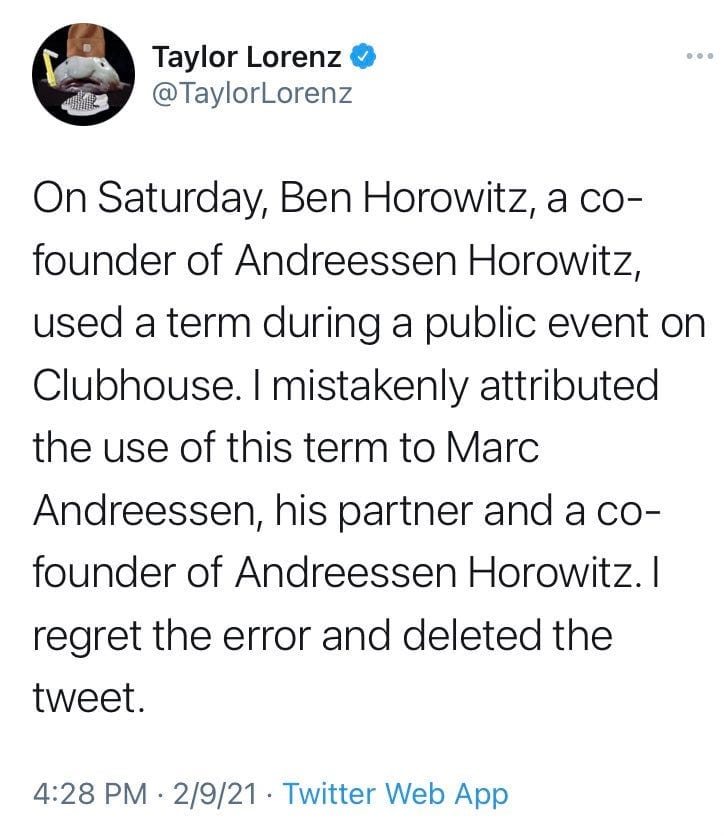

The original situation - and I am loathed to link to Fox News as their bias is, well, obvious - was around Taylor reporting that Marc Andreessen of tech VC Andreessen Horowitz (which I’ll now call A16Z) said the r-slur, when it was actually his partner, Ben Horowitz, who said it. He justified saying it because he was using the moniker (and slur!) that Reddit’s WallStreetBets users refer to them as, specifically asking to hear about the “R-word revolution.”

If you don’t know what Clubhouse is, it’s an app where you can make live voice-based chat rooms where you can talk to other people in them, and people can listen. It is a public forum just like Twitter, except everyone’s talking. Very tiring.

In my unkindest evaluation, Taylor…no, let me stop, I’m not going to let myself be led down bad faith arguments. The general “thing” here that the worst people online are mad about is that Taylor attempted to “cancel” someone, ignoring the fact that someone said a word that sucks, that nobody should say, even if it’s part of this weirdo forums’ language. Her apology - that she misattributed it - is fair, and it’s a tweet, which she clarified then deleted it.

The faux-outrage of people at Taylor misattributing someone also seemed to totally fail to discuss the fact that a major VC used the r-slur. Where’s his apology? I’ve got a disability, and I got called that shit a lot, where’s the apology for that? Where’s the outrage?

I’ll tell you where it is - nowhere! Because the spurious “The NYT is misrepresenting the facts!!!” argument is another chance to dogpile a female reporter for daring to keep tabs on what VCs are saying out loud. She, correctly, thought it was of the public’s interest that a guy wielding billions of dollars' worth of capital was casually throwing around a slur. She misattributed which one of them did it, but yes, it is 100% important that when these people casually, publicly use these terms that they’re called out.

Ultra-poster and supposed cancelee that nevertheless seems to regularly get on TV and make hundreds of thousands of dollars Glenn Greenwald weighed in, perpetuating a thing as “indisputably fabricated” that actually happened, albeit to the other rich white guy from the same VC on the call continued his weirdo fascination with martyrdom and harassment of a female reporter, claiming that Lorenz was wrong for being upset that there was a room called “Taylor Lorenz fans only” which was bashing her - a room that included Marc Andreessen, as well as disgusting racist Charles C. Johnson. Taylor commented the room was bashing her.

People of course nitpicked that Marc had said he was “only there to listen,” as if that is a justification for these actions, and Greenwald referred to Taylor popping in and listening as being a “hall-monitor,” somehow ignoring the fact that a bunch of guys with influence and power were publicly creating an environment that encouraged harassment. Furthermore, if you’re Marc in this case, you have the power to say “let’s rename this group, I don’t want her to get harassed” or like, not be in it, don’t be in the fucking group, your involvement is a tacit acceptance of harassment.

Furthermore, the sneering comment of her being a “hall-monitor” suggests that Clubhouse groups are anything other than public conversations. People joked about DMing her and other things clearly that were negative - and of course, they claimed they were “just jokes.”

Now, imagine if Taylor created a group called “Andreessen Horowitz Fan Club” with a bunch of reporters and made jokes about them. Do you think Greenwald and co. would say that it was harmless, and not listen in? Or would they listen and write down every imagined and real slight, posting them in such a way that makes her look bad?

The problem here is that there is a truly poisonous narrative around who holds the power in these scenarios. The narrative these men want you to absorb is that these venture capitalists are maligned geniuses discussing the future of technology, and there is a nasty lady following them around reporting on them and trying to find a story.

What’s actually happening is they are having a public conversation, via voice. The result is that these conversations are more “free flowing” but also, like all voice-based versus typed communication, are more likely to involve you saying stuff you didn’t think through. It all comes back to my buddy Kasey’s favorite phrase - play stupid games, win stupid prizes. If you’re gonna go on a public forum and just speak whatever words you have in your brain, and those words are not words you wanted to really share with everyone, then you should expect to get called out on it. Furthermore, if you’re a powerful person - say, someone with the ability to control people’s futures by investing (or not investing) in their companies - you should expect people to constantly listen in and report on what you do.

Why We Are Here

What they actually want is reporters to report about them, but not report the bad parts, and make them look good. This is literally my job - pitching people stories that my client can be in that make the client look good and mitigating bad stories - so I am well aware that this is the ideal outcome for a company.

The problem is that the press has become a lot more critical of tech in the last ten years.

When I started my career there were simply more reporters, and more reporters writing more positive stuff. The major media outlets were far happier to write effusive coverage of tech - there was a general hope and positivity around the media that said that, well, we’re all in this together, and we’re all excited to see where this goes. I think the first cracks were when payments company Clinkle raised $25 million, with its CEO winning Forbes 30 under 30 honors, claiming that they could send payments with high-frequency sound. When they actually launched, it was…a prepaid debit program with a bizarre “send a friend a treat” thing I never quite understood, as well as some sort of payments processing company built in. The press had given endless, effusive coverage to a company that never actually seemed to get a product out the door, or really show the product.

Theranos received years of unbelievably positive coverage based on the fact that they said, repeatedly, that you could do blood tests based on a single finger pinprick. The company raised $1.4 billion from huge investors, including DFJ, and even added disgusting villain Henry Kissinger to its board. And why wouldn’t the press trust them? All of these VCs had given all of this money, and thus it’d be insane for anyone to have just entirely falsified their claims, not simply to the press but to investors, again and again and again, right?

Right?

Wrong. The WSJ’s John Carreyrou would blow the story wide open, revealing that Theranos wasn’t even using their own tech, which did not appear to work. The story went very normally from there - most of it was made up, totally misrepresented, and the CEO may go to jail.

Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal was the real nail in the coffin - a clear example of a company that had been given near-unlimited positive coverage that was doing actual, real damage to society.

And let’s not forget Uber, the USAToday 2012 tech company of the year, that under further analysis was barely paying its contractors who they insist are contractors not employees, thus meaning they get no benefits.

In short, three things happened:

- The Tech Press changed from an enthusiast model to an industry model. Where tech previously was treated like games, meaning that you were writing for an audience that required good vibes, you were now writing about tech as an industry - which includes negativity, positivity, and everything in-between.

- Tech became significantly more important, meaning that tech media had a right to be significantly less easy-going on them. There was a previous myth that everyone working on startups was a plucky kid with big dreams. The vast amounts of money and power being wielded are now obvious - the rags to riches myth of startup-making is gone, and this is a multi-trillion dollar industry that has to be treated like one.

- The tech media got burned. These big flameouts - these companies that had been championed for years - it hurts when they turn out to be actually bad. The media has been given many, many reasons to be suspicious of venture backed startups, and are asking, simply, that you back up what you say. If you can’t, well, that’s not good.

Where Does This Clubhouse Thing Fit In?

Back in 2014, I had someone do a dig into how many times anyone had covered or mentioned Box or Dropbox since they’d launched. This extremely rough analysis found that, between 2007 and 2014, TechCrunch alone had covered Dropbox 123 times, and Box.com 98 times. Mathematically - and I am not including the year 2007 in this calculation because Box.net was covered once - that Dropbox was covered at least 1.7 times a month, and Box 1.36 times a month, and almost all of this coverage was entirely positive press. Some years were lighter than others - there are years where Box is covered seven times, some over twenty times - but the point I’m making is that there used to be a point that vast, venture-backed companies could simply roll out releases and get coverage. I am harping on TechCrunch a little hard - the WSJ covered them 13 times in 2013 - but the specific thing I’m talking about is that it was voluminous, positive press. There was not a single article in that time criticizing them, and it seemed any little thing they had to choose was there.

And this is specifically about tech as enthusiast press - enjoying and cheering on the valley it considered itself a part of, which is fine at the time and is not the case anymore. VCs enjoyed relatively turnkey coverage, and would never have called the New York Times names - not when they had Nick Bilton sitting down talking about how great Aaron Levie is. The press were their friends. They were “rooting for them,” and, on the surface, endorsing what they were doing.

Box could get covered for adding a like button to its product, or in the WSJ for adding integrations. I cannot imagine a single company getting a blunt “the next big thing in tech?” headline in the WSJ - no matter how big, no matter how important.

I am not being critical here of any particular outlet - at the time, there were less startups, things looked rosy, and there was an implicit trust between reporters and sources. Tech was by comparison smaller, and people were excited that there was a new way to do things and new people funding them. Also, if you consider what the point of the press is - to inform the public of stuff they should know - they did their job, with the focus on the things they thought were important. It isn’t dishonest, or indeed bad, but while the function didn’t change, the functionality sure did.

Now, things aren’t so easy. You can’t just get covered because you raised money. If you raised money and describe it in a way that’s boring, it won’t get covered. If you raised money and describe it in a way that sounds made up, someone’s going to say you made it up, and if you did, you’re toast. Even if you prove it, a reporter is going to, if they have them, publish their reservations. There were over 200 billion more dollars invested in 2018 than 2008, and enough scandals to make any reporter naturally say “wait a second.” Even if it’s a good investment, there are simply more companies doing more things every day, getting more money, and thus welcoming additional scrutiny.

I don’t have a numerical evaluation of how many investments by A16Z were covered by any particular outlet since 2008, but I’m going to guess the answer is a lot (they invested in Box in 2011). A16Z has benefitted immensely from the positive press in its investments - in Lyft, Facebook, Zynga, Slack, Asana, and others - and watched as the press has changed from a relatively frictionless marketing channel for their investment rounds into something that requires a lot more effort, and isn’t simply an uncritical flume of people saying “damn that’s cool!”

Now, as someone who lived through this change, the natural reaction is yes, your job is harder, but this is not a failure on the part of the reporter. In fact, while my job is slightly harder than it was, I haven’t seen it become impossible, and it’s become a little more fun - I have to read more and understand more to do my job. I have not seen, despite my job being to get the press to cover stuff, the press as having a functional job to cover my stuff - my job is to get them to find it interesting.

I believe that a lot of the people in tech who are having this vacuous, oafish discussion of the media has as “haters” are actually just mad that they can’t say or do what they want and that every action they have isn’t the most important thing in the world. Eric Newcomer wrote a truly bizarre newsletter, discussing in almost magical terms how A16Z was able to get reporters over to their PR person’s house to have nice dinners and meet portfolio companies - a thing that happened not from an abundance of skill but because of an abundance of access. That access was worry-free at the time - a DC-style “we’re all friends here” approach that no longer works, which is now blamed on “not being an exciting upstart” as if that’s something entirely reserved to A16Z and not tech as a whole, declaring, hilariously, that they were “done talking about themselves” on a podcast interview with the press.

It is honestly a reductive strategy. All of those nice dinners and drinks were for nothing if the moment stuff gets hard you turn them into the enemy. Both of you have a job, and making their job - and their lives - easier is how you do it. So you’re mad that they covered one of your portfolio companies negatively - did they get something factually wrong? No? Then change your diaper and move on.

Yes, PR people remain friends with press, and close friends, but the singular expectation of frictionless, positive press has driven a general dislike of the media. They want to make their own media property to “be the go-to place for understanding and building the future,” which betrays a misunderstanding of who reads what and why. People know that things are bad sometimes, and they will still use bad things if they read about them being bad, unless the bad is so bad that they don’t want to use it anymore - and that bad is likely created not by the media, or the reader, or Taylor Lorenz, but by the person doing the bad thing.

It’s, if anything, a tantrum toward truth - believing previously that the media was simply a one-way conduit toward promotion versus a means of promotion that comes through telling a story to someone who likes it. While there are many annoying, extremely loud fanboy types that will continually say something is great despite reality, most readers want to read what they believe is a factually-accurate and hype-free piece. Sure, they want to be excited in some cases - hey, this new gadget is cool! - but they aren’t stupid, and know that things can sometimes be bad.

The funny thing is, all of those relationships could help. You could very easily turn around and say “yeah, I’m self-conscious because now the expectations of me and my investments are different than they were. I’m still adjusting.” And you don’t have to take interviews you believe are going negative. You can prepare for them. You can even participate if you see fit. But it’s gonna happen, and that’s the cost of being famous.

The fear of exposés and investigatory journalism is a rational one, in the sense that nobody wants to have their life rifled through. But the other side of the coin that many VCs have enjoyed - years of effusive press - is that there are now lots of eyeballs, and as tech has got bigger, so has the necessity to keep it in check, which is and always was the job of the reporters.

Treating reporters as ghouls that want something from you is morally wrong and hypocritical of those who hold it, who likely would welcome wanting something from the reporter, say, a positive writeup. The way that Taylor has been treated - someone who has since the day I met her been a genuinely nice, thoughtful and honest person - is disgusting because it shows an utterly usurious taxonomy of the media, as those that are merely pipes to coverage versus walking, talking people that you were actually building a relationship with. If you are so fucking worried about her hearing your conversations, then perhaps there is something in those conversations that you personally need to interrogate, that you are afraid of getting out because you have convinced yourself it’s a good belief to have but realize that very few people agree.

The narrative they want you to have is one of innocent - of being picked apart by the carrion of the media, who simply wish to strip them of all that makes them human - when in fact they are just upset that they are under the scrutiny that their years of using the press to grow earned them. This is the other side of the coin.

Aiding and abetting harassment by “just listening” is an act of cowardice and malice, one that would be disgraceful if you weren’t able to influence and wield billions of dollars and a huge audience. It’s childish, and grotesque, and suggests an inverse of the real power structure - rich men who have attracted other men, some rich, some aspiring to be rich, all of them upset that scrutiny exists in an ecosystem and society that has and will likely continue to benefit them. Can you imagine a less-popular valley CEO or VC getting away with saying the r-word on Twitter, or Clubhouse, or anywhere, really? Even in layers of context?

Yes, there are times where the media have been wrong, and they will gladly admit it. Attempting to lead a miniature war against one woman because you don’t like her listening to your secret boys’ chat that anyone can listen to inspires the wrong kinds of people, and continues to perpetuate power dynamics that do not exist, and never really have.