Soundtrack: Lynyrd Skynyrd — Free Bird

This piece is over 19,000 words, and took me a great deal of writing and research. If you liked it, please subscribe to my premium newsletter. It’s $70 a year, or $7 a month, and in return you get a weekly newsletter that’s usually anywhere from 5000 to 15,000 words, including vast, extremely detailed analyses of NVIDIA, Anthropic and OpenAI’s finances, and the AI bubble writ large. I am regularly several steps ahead in my coverage, and you get an absolute ton of value. In the bottom right hand corner of your screen you’ll see a red circle — click that and select either monthly or annual. Next year I expect to expand to other areas too. It’ll be great. You’re gonna love it.

If you have any issues signing up for premium, please email me at ez@betteroffline.com.

OpenAI told me opex keep eating his revenues, so I asked how many rounds of private equity he has burned and he said he just goes to the market and gets new equity afterwards so I said it sounds like he's just feeding equity to opex and then Sam Altman started crying — @FraPippo428

One time, a good friend of mine told me that the more I learned about finance, the more pissed off I’d get.

He was right.

There is an echoing melancholy to this era, as we watch the end of Silicon Valley’s hypergrowth era, the horrifying result of 15+ years of steering the tech industry away from solving actual problems in pursuit of eternal growth. Everything is more expensive, and every tech product has gotten worse, all so that every company can “do AI,” whatever the fuck that means.

We are watching one of the greatest wastes of money in history, all as people are told that there “just isn’t the money” to build things like housing, or provide Americans with universal healthcare, or better schools, or create the means for the average person to accumulate wealth. The money does exist, it just exists for those who want to gamble — private equity firms, “business development companies” that exist to give money to other companies, venture capitalists, and banks that are getting desperate and need an overnight shot of capital from the Federal Reserve’s Overnight Repurchase Facility or Discount Window, two worrying indicators of bank stress I’ll get into later.

No, the money does not exist for you or me or a person. Money is for entities that could potentially funnel more money into the economy, even if the ways that these entities use the money are reckless and foolhardy, because the system’s intent on keeping entities alive incentivizes it. We are in an era where the average person is told to pull up their bootstraps, to work harder, to struggle more, because, as Martin Luther King Jr. once said, it’s socialism for the rich and rugged free market capitalism for the poor.

The “free market” is a fucking con. When you or I run out of money, our things are taken from us, we receive increasingly-panicked letters, we get phone calls and texts and emails and demands, we are told that all will be lost if we don’t “work it out,” because the financial system is not about an exchange of value but whether or not you can enter into the currently agreed-upon con.

By letting neoliberalism and the scourge of the free markets rule, modern society created the conditions for what I call The Enshittifinancial Crisis — the place at which my friend Cory Doctorow’s Enshittification Theory meets my own Rot Economy Thesis in a fourth stage of Enshittification.

Enshittification unfolds in three phases: first, a company is “good to users,” Doctorow writes, drawing people in droves, as funnel traps do Japanese beetles, with the promise of connection or convenience. Second, with that mass audience consolidated, the company is “good to business customers,” compromising some of its features so that the most lucrative clients, usually advertisers, can thrive on the platform. This second phase is the point at which, say, our Facebook feeds fill with ads and posts from brands. Third, the company turns the user experience into “a giant pile of shit,” making the platform worse for users and businesses alike in order to further enrich the company’s owners and executives.

I’ll walk you through it.

Facebook was a huge, free platform, much like Instagram, that offered fast and easy access to everybody you knew. It acquired Instagram in 2012 to kill off a likely competitor, and over time would start making both products worse — clickbait notifications, a mandatory algorithmic feed that deliberately emotionally manipulated people and stoked political division, eventually becoming full of AI slop and videos, all so that Meta could continue to sell billions of dollars of ads a quarter. Per Kyle Chayka of the New Yorker, “Facebook’s feed, now choked with A.I.-generated garbage and short-form videos, is well into the third act of enshittification.”

The third stage is critical, in that it’s when the company also turns on its business customers. A Marketing Brew story from September of last year told the tale of multiple advertisers who found their campaigns switching to different audiences, wasting their money and getting questionable results. A New York Times story from 2021 described companies losing upwards of 70% of their revenue during a Facebook ads outage, another from 2018 described how Meta (then Facebook) deliberately hid issues with its measurement of engagement on videos from advertisers for over a year, and more recently, Meta’s ads tools started switching out top-performing ads with AI-generated ones, in one case targeting men aged 30 to 45 with an AI-generated grandma, all without warning the advertiser.

Meta doesn’t give a shit, because investors and analysts don’t give a shit. I could say “sell-side analysts” here — the ones that are trying to get you to buy a stock — but based on every analyst report I’ve read from a major bank or hedge fund, I truly think everybody is complicit.

In November 2025, Reuters revealed that Meta projected in late 2024 that 10% of its annual revenue ($16 billion) would come from advertisements for scams or banned goods, mere weeks after Meta announced a ridiculous $27 billion data center debt package, one that used deep accountancy magic to keep it off of its balance sheet despite Meta guaranteeing the entirety of the loan.

One would think this would horrify investors for two reasons:

- Meta’s business is both supporting and profiting from organized crime, and at 10% of its revenue, it’s also kind of dependent on it.

- Meta is using deliberate and insidious accounting tricks to act like a data center that it is paying to build and will be the sole tenant of is somehow an “off balance sheet” operation.

One would be wrong. Morgan Stanley said a few weeks ago that it is “one of the handful of companies that can leverage its leading data, distribution and investments in AI,” and raised its target to $750, with a $1000-a-share bull case. Wedbush raised Meta’s price to $920, and Bank of America staunchly held firm at…$810. I can find no analyst commentary on Meta making sixteen billion dollars on fraud, because it doesn’t matter to them, because this is the Rot Economy, and all that matters is number go up.

Reality — such as whether there’s any revenue in AI, or whether it’s a good idea that Meta is spending over $70 billion this year on capital expenditures on a product that has generated no revenue (and please, fucking spare me the bullshit around “Meta’s AI ads play,” that whole story is nonsense) — doesn’t matter to analysts, because stocks are thoroughly, inextricably enshittified, and analysts don’t even realize it’s happening.

The Great Enshittification Of The Stock Market

The stages of enshittification usually involve some sort of devil’s deal.

- In Stage 1, things are good for users: the platform is free, things are easy-to-use, and thus it’s really simple for you and your friends to adopt and become dependent on it.

- In Stage 2, things become bad for consumers, but good for business customers: the platform begins forcing users to do “profitable” things — like show them more adverts by making search results worse — all while making it difficult to migrate to another one, either through locking in your data or the tacit knowledge that moving platforms is hard, and your friends are usually in one place. Businesses sink tons of money into the platform, knowing that users are unlikely to leave, and make good money buying ads against a populace that increasingly stays because it has to as there are no other options.

- In Stage 3, things become bad for consumers and businesses, but good for shareholders: the platforms begin to deteriorate to the point that usability is pushed to the brink, and businesses — who are now dependent on the platform because monopolies have pushed out every alternative platform to advertise or reach consumers — begin to see their product crumble, all in favour of shareholder capital, which only cares about stock value, net income and buybacks.

We have now entered Enshittification Stage 4, where businesses turn on shareholders.

Analysts and investors have become trapped in the same kind of loathsome platform play as consumers and businesses, and face exactly the same kinds of punishment through the devaluation of the stock itself. Where platforms have prioritized profits over the health and happiness of users or business customers, they are now prioritizing stock value over literally anything, and have — through the remarkable growth of tech stocks in particular — created a placated and thoroughly whipped investor and analyst sect that never asks questions and always celebrates whatever the next big thing is meant to be.

The value of a “stock” is not based on whether the business is healthy, or its future certain, but on its potential price to grow, and analysts have, thanks to an incredible bull run of tech stocks going on over a decade, been able to say “I bet software will be big” for most of the time, going on CNBC or Bloomberg and blandly repeating whatever it is that a tech CEO just said, all without any worries about “responsibility” or “the truth.”

This is because big tech stocks — and many other big stocks, if I’m honest — have made their lives easy as long as they don’t ask questions. Number always seems to be going up for software companies, and all you need to do is provide a vociferous defense of the “next big thing,” and come up with a smart-sounding model that justifies eternal growth.

This is entirely disconnected from the products themselves, which don’t matter as long as Number Go Up. If net income is high and the company estimates it will continue to grow, then the company can do whatever the fuck it want with the product it sells or the things that it buys. Software Has Eaten The World in the sense that Andreesen got his wish, with investors now caring more about the “intrinsic value” of software companies rather than the businesses or products themselves.

And because that’s happening, investors aren’t bothering to think too hard about the tech itself, or the deteriorating products underlying tech companies, because “these guys have always worked it out” and “these companies have always managed to keep growing.” As a result, nobody really looks too deep. Minute changes to accounting in earnings filings are ignored, egregious amounts of debt are waved off, and hundreds of billions of dollars of capital expenditures are seen as “the new AI revolution” versus “a huge waste of money.”

By incentivizing the Rot Economy — making stocks disconnected from the value of the company beyond net income and future earnings guidance — companies have found ways to enshittify their own stocks, and shareholders will be the ones who suffer, all thanks to the very downstream pressure that they’ve chosen to ignore for decades.

You see, while one might (correctly) see that the deterioration of products like Facebook and Google Search was a sign of desperation, it’s important to also see it as the companies themselves orienting around what they believe analysts and investors want to see.

You can also interpret this as weakness, but I see it another way: stock manipulation, and a deliberate attempt to reshape what “value” means in the eyes of customers and investors. If the true value of a stock is meant to be based on the value of its business, cash flow, earnings and future growth, a company deliberately changing its products is an intentional interference with value itself, as are any and all deceptive accounting practices used to boost valuations.

But the real problem is that analysts do not…well…analyze, not, at least, if it goes against the market consensus. That’s why Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan and Futurum and Gartner and Forrester and McKinsey and Morgan Stanley all said that the metaverse was inevitable — because they do not actually care about the underlying business itself, just its ability to grow on paper.

Need proof that none of these people give a fuck about actual value? Mark Zuckerberg burned $77 billion on the metaverse, creating little revenue or shareholder value and also burning all that money without any real explanation as to where it went.

The street didn’t give a shit because meta’s existent ads business continued to grow, same as it didn’t give a shit that Mark Zuckerberg burned $70 billion on capex, even though we also really don’t know where that went either.

In fact, we really have no idea where all this AI spending is going. These companies don’t tell us anything. They don’t tell us how many GPUs they have, or where those GPUs are, or how many of them are installed, or what their capacity is, or how much money they cost to run, or how much money they make. Why would we? Analysts don’t even look at earnings beyond making sure they beat on estimates. They’ve been trained for 20 years to take a puddle-deep look at the numbers to make sure things look okay, look around their peers and make sure nobody else is saying something bad, and go on and collect fees.

The same goes for hedge funds and banks propping up these stocks rather than asking meaningful questions or demanding meaningful answers. In the last two years, every major hyperscaler has extended the “useful life” of its servers from 3 years to either 5.5 or 6 years — and in simple terms, this allowed them to incur a smaller depreciation expense each quarter as a result, boosting net income. Those who are meant to be critical — analysts and investors sinking money into these stocks — had effectively no reaction, despite the fact that Meta used (per the Wall Street Journal) this adjustment to reduce its expenses by $2.3 billion in the first three quarters of this year.

This is quite literally disconnected from reality, and done based on internal accounting that we are not party to. Every single tech firm buying GPUs did this and benefited to the tune of billions of dollars in decreased revenues, and analysts thought it was fine and dandy because number went up.

Shareholders are now subordinate to the shares themselves, reacting in the way that the shares demand they do, being happy for what the companies behind the shares give them, and analysts, investors and even the media spend far more energy fighting the doubters than they do showing these companies scrutiny.

Much like a user of an enshittified platform, investors and analysts are frogs in a pot, the experience of owning a stock deteriorating since Jack Welch and GE taught corporations that the markets are run with the kind of simplistic mindset built for grifter exploitation.

And much like those platforms, corporations have found as many ways as possible to abuse shareholders, seeing what they can get away with, seeing how far they can push things as long as the numbers look right, because analysts are no longer looking for sensible ideas.

Let me give you an example I’ve used before. Back in November 1998, Winstar Communications signed a “$2 billion equipment and finance agreement with Lucent Technologies” where Winstar would borrow money from Lucent to buy stuff from Lucent, all to create $100 million in revenue over 5 years.

In December 1999, Barron’s wrote a piece called “In 1999 Tech Ruled”:

George Gilbert, who manages the Northern Technology Fund , predicts the Web-centric worlds of consumer services and software will fare well next year, too.

"A lot of people are increasing their access to the Internet," says Gilbert. "And e-commerce and business networking are very high priorities for the Fortune 100."

Lawrence York, lead portfolio manager of the WWW Internet Fund, is bullish on semiconductors, telecommunications and business-to-business – or B2B – e-commerce software. But he's wary of online retailers. "That model won't work long term," he asserts.

His top B2B picks? Ariba and Official Payments. In wireless, he likes Winstar , Ciena and AirNet Communications , which went public earlier this month.

Airnet? Bankrupt. WinStar? Horribly bankrupt. While Ciena survived, it had spent over a billion dollars to acquire other companies (all stock, of course), only to see its revenue dwindle basically overnight from $1.6bn to $300 million as the optical cable industry collapsed.

One would have been able to work out that Winstar was a dog, or that all of these companies were dogs, if you were to look at the numbers, such as “how much they made versus how much they were spending.” Instead, analysts, the media and banks chose to pump up these stocks because the numbers kept getting bigger, and when the collapse happened, rationalizations were immediately created — there were a few bad apples (Enron, Winstar, WorldCom), “the fiber was useful” and thus laying it was worthwhile, and otherwise everything was fine.

The problem, in everybody else’s mind, was that everybody had got a bit distracted and some companies that weren’t good would die. All of that lost money was only a problem because it didn’t pay off. This was a misplaced gamble, and it taught tech executives one powerful lesson: earnings must be good, without fail, by any means necessary, and otherwise nothing else matters to Wall Street.

It’s all about incentives. A sell-side analyst that tells you not to buy something is a problem. A journalist that is skeptical or critical of an industry in the midst of a growth or hype cycle is considered a “hater” — don’t I fucking know it. Analysts that do not sing the same tune as everybody else are marginalized, mocked and aggressively policed.

And I don’t fucking care. Stop being fucking cowards. By not being skeptical or critical you are going to lead regular people into the jaws of another collapse.

The dot com bubble was actually a great time to start reevaluating how and why we value stocks — to say “hey, wait, that $2 billion deal will only make $100 million in revenue?” or “this company spends $5 for every $1 it makes!” — but nobody, it appears, remained particularly suspicious of the tech industry, or a stock market that was increasingly orienting itself around conning shareholders.

And because shareholders, analysts and the media alike refused to retain a single shred of suspicion leaving the dot com era, the mania never actually subsided. Financial publications still found themselves dedicated to explaining why the latest hype cycle was real. Journalists still found themselves told by editors that they had to cover the latest fad, even if it was nonsensical or clearly rotten. Analysts still grabbed their swords and rushed to protect the very companies that have spent decades misleading them.

Much like we spent years saying that Facebook was a “good deal” because it was free, analysts and investors say tech stocks are “great to hold” because they kept growing, even if the reason they “kept growing” was a series of interlocking monopolies, difficult-to-leave platforms and impossible-to-fight traction and pricing, all of which have an eventual sell-by date.

I realize I’m pearl-clutching over the amoral status of capitalism and the stock market, but hear me out: what if we’re actually in a 15-to-20-year-long knife-catching competition? What if all anybody has done is look at cashflow, net income, future growth guidance, and called it a day? A lack of scrutiny has allowed these companies to do effectively anything they want, bereft of worrisome questions like "will this ever make a profit?"

What if we basically don’t know what the fuck is going on? What if all of this was utterly senseless?

AI Accelerated The Enshittification Of The Stock Market

As I wrote last year, the tech industry has run out of hypergrowth ideas, facing something I call “the Rot Com bubble.” In simple terms, they’re only “doing AI” because there do not appear to be any other viable ideas to continue the Rot Economy’s eternal growth-at-all-costs dance.

Yet because growth hasn’t slowed yet, analysts, the media and other investors are quick to claim that AI is “paying off,” even if nobody has ever said how much AI revenue is being generated or, in the case of Salesforce, they can say “nearly $1.4 billion ARR,” which sounds really big until you realize a company with $10.9 billion in revenue is boasting about making less than $116 million in revenue in a month.

Nevertheless, because Salesforce set a new revenue target of $60 billion by 2030, the stock jumped 4%. It doesn’t matter that most Agentforce customers don’t pay for the service, or that AI isn’t really making much money, or really anything, other than Number Go Up.

The era we live in is one of abject desperation, to the point that analysts and investors — and shareholders by extension — will take any abuse from management. They will allow companies to spend as much money as they want in whatever ways they want, as long as it continues the charade of “number go up.”

Let me spell it out a little more, using the latest earnings of various hyperscalers as an example.

- According to its latest quarterly filings, Microsoft spent $34.9 billion on capital expenditures, Amazon $34.2 billion, Meta $19.37 billion, and Google $24 billion.

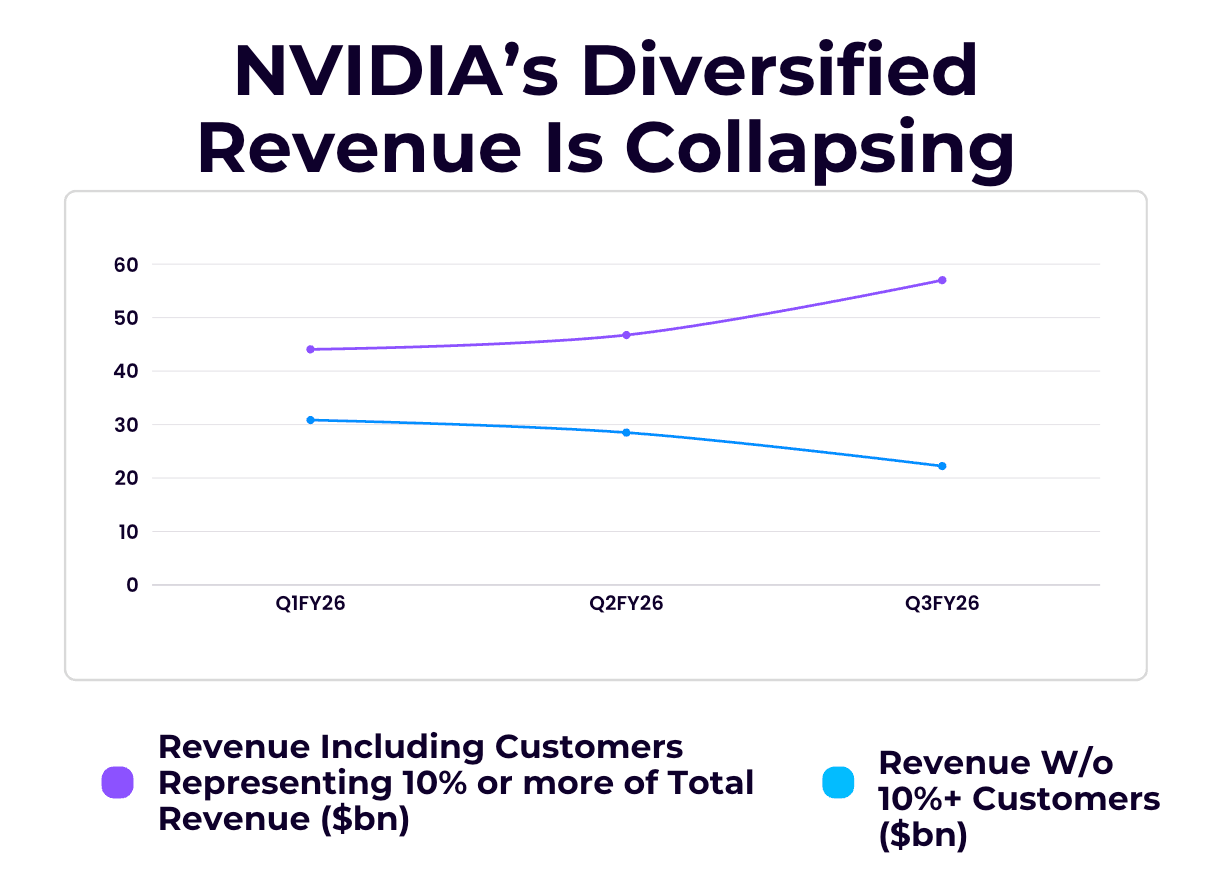

- The common mantra is that these companies are “spending all this money on GPUs,” but that doesn’t match up with NVIDIA’s revenues. NVIDIA’s last quarterly earnings said that four direct customers made up more than 10% of revenue — 22% ($12.54bn), 15% ($8.55bn), 13% ($7.41bn) and 11% ($6.27bn) out of $57 billion.

- While this sort of lines up with capex spend, it doesn’t if you shift back a quarter, when Microsoft spent $21.4 billion, Meta $17.01 billion, Amazon $31.4 billion and Google $22.4 billion, with the vast majority on “technical infrastructure.”

- In the same quarter, NVIDIA had only two customers that accounted for more than 10% — one 23% ($10.7bn) and one 16% ($7.47bn) out of $46.7 billion.

- Another quarter back, and Microsoft spent $22.6 billion, Meta $13.69 billion, Google $17.2 billion and Amazon $22.4 billion.

- In the same quarter, NVIDIA had two customers accounting for more than 10% of revenue — 16% ($7.49bn) and 14% ($6.168bn).

- While this sort of lines up with capex spend, it doesn’t if you shift back a quarter, when Microsoft spent $21.4 billion, Meta $17.01 billion, Amazon $31.4 billion and Google $22.4 billion, with the vast majority on “technical infrastructure.”

- Where, exactly, is all this money going? In Microsoft’s latest earnings (Q1FY26), it said that $19.39 billion went to “additions to property and equipment,” with “roughly half of [its total capex] spend on short-lived assets, primarily GPUs and CPUs.” A quarter (Q4FY2025) back, additions to property and equipment were $16.74 billion, with “roughly half…[spent] on long-lived assets that will support monetization over the next 15 years and beyond.”

- Let’s assume that Microsoft is NVIDIA’s biggest customer every single quarter — customer A, spending $12.5 billion (out of $34.9 billion), $10.7 billion (out of $21.4 billion) and $7.049 billion (out of $22.6 billion) a quarter.

- Assuming that Microsoft is only buying NVIDIA’s Blackwell GPUs (forgive the model numbers, but it’s based on my own modeling. Let’s say 40% B200s, 30% GB200s, 10% B300s and 20% GB300s), that works out to about 457MW of IT load for Q1FY26, 391MW for Q4FY25 and (adjusting to include more H200s, as the B300/GB300s were not shipping yet) 263MW for Q3FY25.

- Has Microsoft built 1.11GW of data centers in that time? Apparently! It claims it added 2GW in the last year, but Satya Nadella claimed in November that Microsoft had chips in inventory it couldn’t install due to a lack of power.

- In any case, where did the remaining $22.4 billion, $11.9 billion and $15.5 billion in capex flow? We know there are finance leases. What for? More GPUs? What is the actual output of these expenditures?

We have no idea, because analysts and investors are in an abusive relationship with tech stocks. It is fundamentally insane that Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google have spent $776 billion in capital expenditures in the space of three years, and even more so that analysts and investors, when faced with such egregious numbers, simply sit back and say “they’re building the infrastructure of the future, baby!” Analysts and traders and investors and reporters do not think too hard about the underlying numbers, because doing so immediately makes you run head-first into a number of worrying questions such as “where did all that money go?” and “will any of this pay off?” and “how many GPUs do they actually own?”

Analysts have, on some level, become the fractional marketing team for the stocks they’re investing in. When Oracle announced its $300 billion deal with OpenAI in September — one that Oracle does not have the capacity to fill and OpenAI does not have the money to pay for – analysts heaved and stammered like horny teenagers seeing their first boob:

John DiFucci from Guggenheim Securities said he was “blown away.” TD Cowen’s Derrick Wood called it a “momentous quarter.” And Brad Zelnick of Deutsche Bank said, “We’re all kind of in shock, in a very good way.”

“There’s no better evidence of a seismic shift happening in computing than these results that you just put up,” Zelnick said on the earnings call.

These are the same people that retail and institutional investors rely upon for advice on what stocks to buy, all acting with the disregard for the truth that comes from years of never facing a consequence. Three months later, and Oracle has lost basically all of the stock bump it saw from the OpenAI deal, meaning that any retail investor that YOLO’d into the trade because, say, analysts from major institutions said it was a good idea and news outlets acted like this deal was real, already got their ass kicked.

And please, spare me the “oh they shouldn’t trade off of analysts” bullshit. That’s the kind of victim-blaming that allows these revered fuckwits to continue farting out these meaningless calls.

In reality, we’re in an era of naked, blatant, shameless stock manipulation, both privately and publicly, because a “stock” no longer refers to a unit of ownership in a company so much as it is a chip at a casino where the house constantly changes the rules. Perhaps you’re able to occasionally catch the house showing its hand, and perhaps the house meant for you to see it. Either way, you are always behind, because the people responsible for buying and selling stocks at scale under the auspices of “knowing what’s going on” don’t seem to know what they’re talking about, or don’t care to find out.

Let’s walk through the latest surge of blatant stock manipulation, and how the media and analysts helped it happen.

Oracle, September 10 2025

Oracle announces its unfillable, unpayable $300 billion deal with OpenAI, leading to 30%+ bump in stock price. Analysts, who should ostensibly be able to count, call it “momentous” and say they’re “in shock.” On September 22 2025, CEO Safra Catz steps down, and nobody seems to think that’s weird or suspicious.

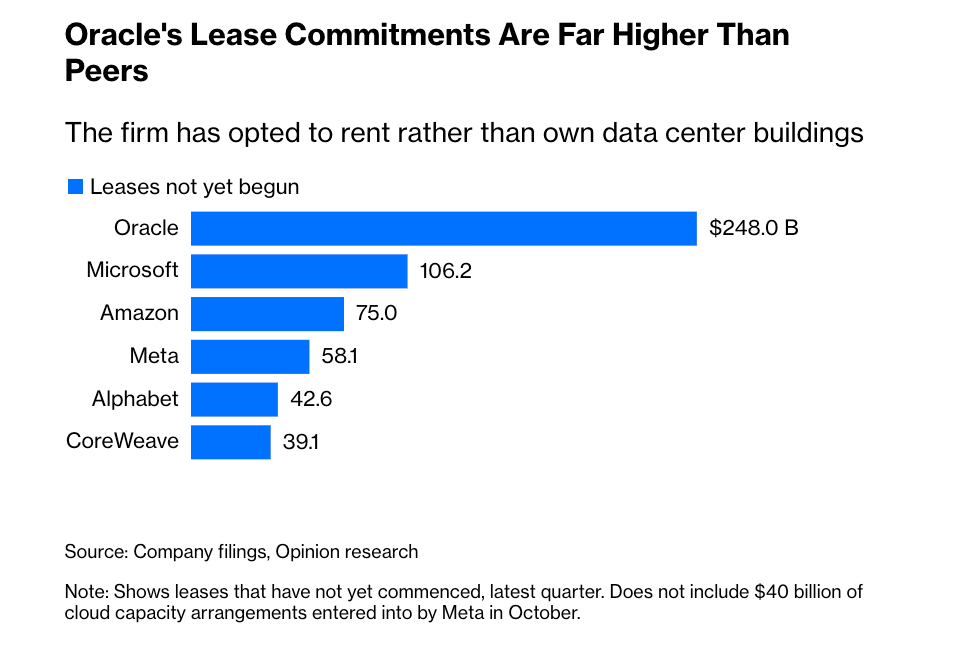

Two months later, Oracle’s stock is down 40%, with investors worried about Oracle’s growing capex, which is surprising I suppose if you didn’t think about how Oracle would build the fucking data centers.

Basically anyone who traded into this got burned.

NVIDIA, September 22 2025

NVIDIA announced a “strategic partnership” to invest “up to $100 billion” and build 10GW of data centers with OpenAI, with the first gigawatt to be deployed in the second half of 2026. Where would the data centers go? How would OpenAI afford to build them? How would OpenAI build a gigawatt in less than a year? Don’t ask questions, pig!

NVIDIA’s stock bumped from from $175.30 to $181 in the space of a day. The media wrote about the story as if the deal was done, with CNBC claiming that “the initial $10 billion tranche [was] expected to close within a month or so once the transaction has been finalized.” I read at least ten stories that said that “NVIDIA had invested $100 billion.”

Analysts would say that NVIDIA was “locking in OpenAI” to “remain the backbone of the next-gen AI infrastructure,” that “demand for NVIDIA GPUs is effectively baked into the development of frontier AI models,” that the deal “[strengthened] the partnership between the two companies…[and] validates NVIDIA’s long-term growth numbers with so much volume and compute capacity.” Others would say that NVIDIA was “enabling OpenAI to meet surging demand.”

Three analysts — Rasgon at Bernstein, Luria at D.A. Davidson and Wagner at Aptus Capital — all raised circular deal concerns, but they were the minority, and those concerns were still often buried under buoyant optimism about the prospects of the company.

One eensy weensy problem though, everyone! This was a “letter of intent” — it said so in the announcement! — and on NVIDIA’s November earnings, it said that it “entered into a letter of intent with an opportunity to invest in OpenAI.”

It turns out the deal didn’t exist and everybody fell for it! NVIDIA hasn’t sent a dime and likely won’t. A letter of intent is a “concept of a plan.”

SK Hynix, Samsung, October 1 2025

Back in October, Reuters reported that Samsung and SK Hynix had "signed letters of intent to supply memory chips for OpenAI's data centers," with South Korea's presidential office saying that said chip demand was expected to reach "900,000 wafers a month," with "much of that from Samsung and SK Hynix," which was quickly extrapolated to mean around 40% of global DRAM output.

Stocks in both companies, to quote Reuters, “soared,” with Samsung climbing 4% and SK Hynix more than 12% to an all-time high. Analyst Jeff Kim of KB Securities said that “there have been worries about high bandwidth memory prices falling next year on intensifying competition, but such worries will be easily resolved by the strategic partnership,” adding that “Since Stargate is a key project led by President Trump, there also is a possibility the partnership will have a positive impact on South Korea's trade negotiations with the U.S.”

Donald Trump is not “leading Stargate.” Stargate is a name used to refer to data centers built by OpenAI. KB Securities has around $43 billion of assets under management. This is the level of analysis you get from these analysts! This is how much they know!

On SK Hynix's October 29 2025 earnings call, weeks after the announcement, its CEO, Kim Woo-Hyun, was asked a question about High Bandwidth Memory growth by SK Kim from Daiwa Securities:

Kim: Thank you very much for taking my question. It is on demand. Now, there have been a series of announcements of GPU and ASIC supply cooperation between Big Techs and AI companies, fueling expectations of further AI market growth. Then, against this backdrop, what is the company's outlook on HBM demand growth, as well as a broadening of the customer base?

SK Hynix: Thank you for the question. Now, with upward adjustment in Big Tech's CapEx and increased investment by AI companies, the HBM market, even by a conservative estimate, will keep growing at an average of over 30% for the next five years.

I will point to our recent LOI with OpenAI for large-scale DRAM supply as an example of the very strong market demand for AI, as well as the need to secure AI memory based on HBM more than anything else when developing AI technology.

This is the only mention of OpenAI. Otherwise, SK Hynix has not added any guidance that would suggest that its DRAM sales will spike beyond overall growth, other than mentioning it had "completed year 2026 supply discussions with key customers." There is no mention of OpenAI in any earnings presentation.

On Samsung's October 30 2025 earnings call, Samsung mentioned the term "DRAM" 18 times, and neither mentioned OpenAI nor any letters of intent.

In its Q3 2025 earnings presentation, Samsung mentions it will "prioritize the expansion of the HBM4 [high bandwidth memory 4] business with differentiated performance to address increasing AI demand."

Analysts do not appear to have noticed a lack of revenue from an apparent deal for 40% of the world’s RAM! Oh well! Pobody’s nerfect!

Both Samsung and SK Hynix’s stocks have continued to rise since, and you’d be forgiven for thinking this deal was something to do with it, even though it wasn’t.

AMD, October 5, 2025

AMD announced that it had entered a “multi-year, multi-generation agreement” with OpenAI to build 6 GW of data centers, with “the first 1GW deployment set to begin in the second half of 2026,” calling the agreement “definitive” with terms that allowed OpenAI to buy up to 10% of AMD’s stock, vesting over “specific milestones” that started with the first gigawatt of data center development. Said data centers would also use AMD’s yet-to-be-released MI450 GPUs. The deal would, per Reuters, bring in “tens of billions of dollars of revenue.”

Where would those data centers go? How would OpenAI pay for them? Would the chips be ready in time? Silence, worm! How dare you ask questions? How dare you? Why are you asking questions? NUMBER GO UP!

AMD’s shares surged by 34%, with analyst Dan Ives of Wedbush saying that this was a “major valuation moment” for AMD. As an aside, Ives said that NVIDIA would benefit from the metaverse in 2021, and told CBS News in November 22 2021 that “the metaverse [was] real and Wall Street [was] looking for winners.”

One would think that AMD’s November earnings — a month after the announcement — might be a barn-burner full of remaining performance obligations from OpenAI. In fact, CEO Lisa Su said that “[AMD expected] this partnership will significantly accelerate [its] data center AI business, with the potential to generate well over $100 billion in revenue over the next few years.”

Here’s how AMD’s 10-Q filing referred to it:

As of September 27, 2025, the aggregate transaction price allocated to remaining performance obligations under contracts with an original expected duration of more than one year was $279 million, of which $139 million is expected to be recognized in the next 12 months. The revenue allocated to remaining performance obligations does not include amounts which have an original expected duration of one year or less.

…so, no revenue from OpenAI at all, I guess? AMD raised guidance by 35% over the next five years AMD's trailing 12-month revenue is $32 billion. "Tens of billions of dollars" would surely lead to more than a 35% boost (an increase of $11.2 billion or so) in the next five years?

Guess all of that was for nothing. No follow-up from the media, no questions from analysts, just a shrug and we all move on.

Anyway, AMD’s stock is now down from a high of $259 at the end of October to around $214 as of writing this sentence. Everybody who traded in based on analyst and media comments got fucked.

Broadcom, October 13, 2025

So, back on September 5, Broadcom said on its earnings call that it had a $10 billion order from a mystery customer, which analysts quickly assumed was OpenAI, leading to the stock popping 9%, and gradually increasing to a high of $369 or so on September 10, before declining a little until October 13, when Broadcom announced its ridiculous 10 gigawatt deal with OpenAI, claiming that it would deploy 10GW of OpenAI-designed chips, with the first racks to deploy the second half of 2026 and the entire deployment completed by end of 2029.

The same day, its president of semiconductor solutions Charlie Kawwas added that said mystery customer was actually somebody else:

“I would love to take a $10 billion [purchase order] from my good friend Greg [Brockman, COO of OpenAI],” Kawwas said. “He has not given me that PO yet.”

Nevertheless, Broadcom's stock popped by 9% on the news about the 10GW deal, with CNBC adding that "the companies have been working together for 18 months." Because it's OpenAI, nobody sat and thought about whether somebody at Broadcom saying "well, OpenAI has yet to order these chips yet" was a problem. In fact, the answer to “how does OpenAI afford this?” appeared to be “they’d afford it” when it came to analysts:

The 2026 timeline set out by OpenAI for the build-out is aggressive, but the startup is also best positioned to raise the funds required for the project, given the heights of investor confidence, said Gadjo Sevilla, an analyst at eMarketer.

"Financing such a large chip deal will likely require a combination of funding rounds, pre-orders, strategic investments, and support from Microsoft (MSFT.O), as well as leveraging future revenue streams and potential credit facilities."

Not to worry, OpenAI’s solution was far simpler: it didn’t order any chips. During Broadcom's November earnings call, where Broadcom revealed that the $10 billion order was actually from Anthropic, another LLM startup that burns billions of dollars, which was buying Google's TPUs, and also booked another $11 billion in orders. Analysts somehow believed that Anthropic is “positioned to spend heavily” despite being another venture-backed welfare recipient in the same flavor as OpenAI.

Oh, right, that 10GW OpenAI deal. Broadcom CEO Hock Tan said that he did “not expect much in 2026” from the deal, and guidance did not change to reflect it.

Broadcom climbed to a high of $412 leading up to its earnings, and I imagine it did so based on people trading on the belief that OpenAI and Broadcom were doing a deal together, which does not appear to be happening. While there’s an alleged $73 billion backlog, every dollar from Anthropic is questionable.

But Ed, We Can’t Distrust Public Companies!

Actually, yes we can.

Whenever a company says “letter of intent” — as NVIDIA and SK Hynix/Samsung did — it’s important to immediately stop taking the deal seriously until you get the word “contract” involved. Not “agreement” or “deal” or “announcement,” but “contract,” because contracts are the only thing that actually matters.

Similarly, it’s time for everybody — analysts, the media, members of congress, the fucking pope, I don’t care — to start treating these companies with suspicion, and to start demanding timelines. NVIDIA and Microsoft announced their $15 billion investment in Anthropic over a month ago. Where’s the money? Why does the agreement say “up to $10 billion” for NVIDIA and “up to $5 billion” from Microsoft? These subtle details suggest that the deal is not going to be for $15 billion, and the lack of activity suggests it might not happen at all.

These deals are announced with the intention of suggesting there is more revenue and money in generative AI than actually exists. Furthermore, it is irresponsible and actively harmful for analysts and the media to continually act as if these deals will actually get paid when you consider the financial conditions of these companies.

As part of its alleged funding announcement with NVIDIA and Microsoft, Anthropic agreed to purchase $30 billion of Azure compute. It also agreed to spend "tens of billions of dollars" with Google Cloud. It ordered $10 billion in chips from Broadcom earlier in the year, and apparently placed another $11 billion order in its latest fiscal quarter. How does it pay for those? It allegedly will burn $2.8 billion this year (I believe it burned much, much more) and raised $16.5 billion in funding (before Microsoft and NVIDIA’s involvement, which we cannot confirm has actually happened). How are investors tolerating Broadcom not directly stating “the future financial condition of this company is questionable”? Has Broadcom created a reserve for this deal?

If not, why not? Anthropic will make no more than $5 billion this year, and has raised $17.5bn (with a further $2.5bn coming in the form of debt). How can it foreseeably afford to pay $10 billion, or $11 billion, or $21 billion, considering its already massive losses and all those other obligations mentioned? Will Jensen Huang hand over $10 billion so that Anthropic can hand it to Broadcom?

I realize the counter-argument is that companies aren’t responsible for their counterparties’ financial health, but my argument is that it’s the responsibility of any public company to give a realistic view of its financial health, which includes noting if a chunk of its revenue is from a startup that can’t afford to pay for its orders. There is no counter to that! Anthropic cannot afford to pay Broadcom $10 billion right now!

Nevertheless, the problem is that in any bubble, being really stupid and ignorant works right up until it doesn’t, and however harsh the dot com bubble might have been, it wasn’t harsh enough and those who were responsible were left unpunished and unashamed, guaranteeing that this cycle would happen again.

I want to be really, abundantly clear about what’s happening: every single stock you see “growing because of AI” outside of those selling RAM and GPUs is actually growing because of something else. Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Meta all have other products that are making them money. AI is not doing it, and because analysts and investors do not think about things for two seconds, they have allowed themselves to be beaten down and turned into supplicants for public stocks.

Investors have allowed themselves to be played, and the results will be worse than the dot com bubble bursting by several echelons.

The Great Enshittifinancial Crisis

AI Is An Existential Threat To Venture Capital

I’m gonna be really simplistic for a second.

I am skeptical of AI because everybody loses money. I believe every AI company is unprofitable with margins that are getting increasingly worse as they scale, and as a result that none of them will be able to either get acquired or go public.

Sidenote: This was always the way that venture worked — pump up an unprofitable startup, then sell it to a hyperscaler or take it public, and then let the rest of the world deal with the toxic asset until it either died or wasn’t toxic anymore.

This means that venture capitalists that have sunk money into AI stocks are going to be sitting on a bunch of assets under management (AUM) — the same assets they collect fees on — that will eventually crater or go to zero, because there will be no way for any liquidity event to occur.

This is at a time of historically-low liquidity for venture capitalists, with Pitchbook estimating there will only be $100.8 billion in venture capital funds available at the end of 2025.

Venture capitalists raise money from limited partners, who invest in venture capital with the hope of returns that outpace investing in the public markets. Venture capital vastly overinvested during 2021 and 2022, This was also a problem in private equity. In simple terms, this means these funds are sitting on tons of stock that they cannot shift, and the longer it takes for a company to either go public or acquired, the more likely it is the VC or PE firm will have to mark down its value.

This is so bad that according to Carta, as of August 2024, less than 10% of VC funds raised in 2021 have made any distributions to their investors. In a piece from September, Carta revealed that “about 15% of funds” from 2023 have generated any disbursements as of Q2 2025, and the median net internal rate of return was a median 0.1%, meaning that, at best, most investors got their money back and absolutely nothing else.

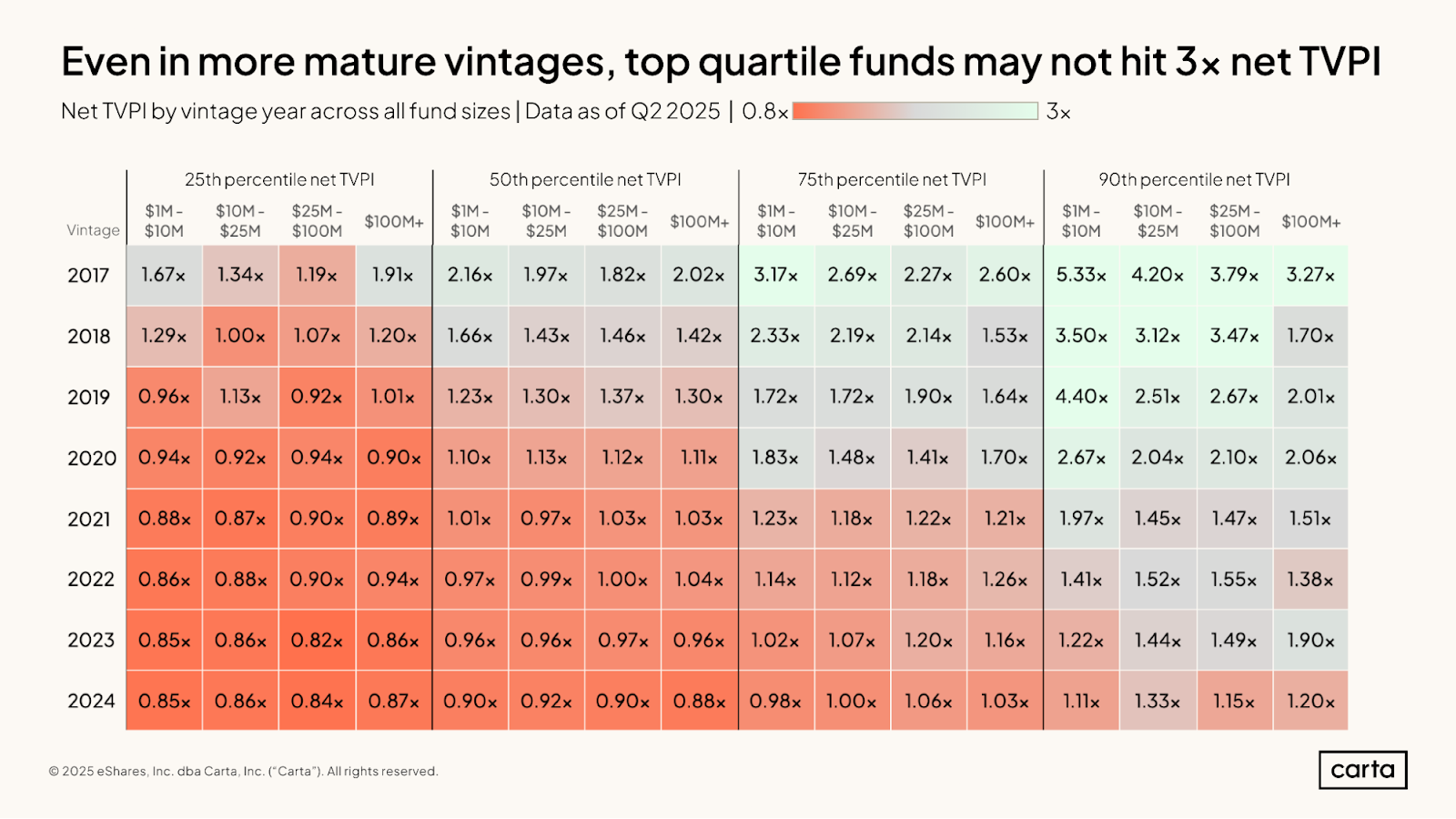

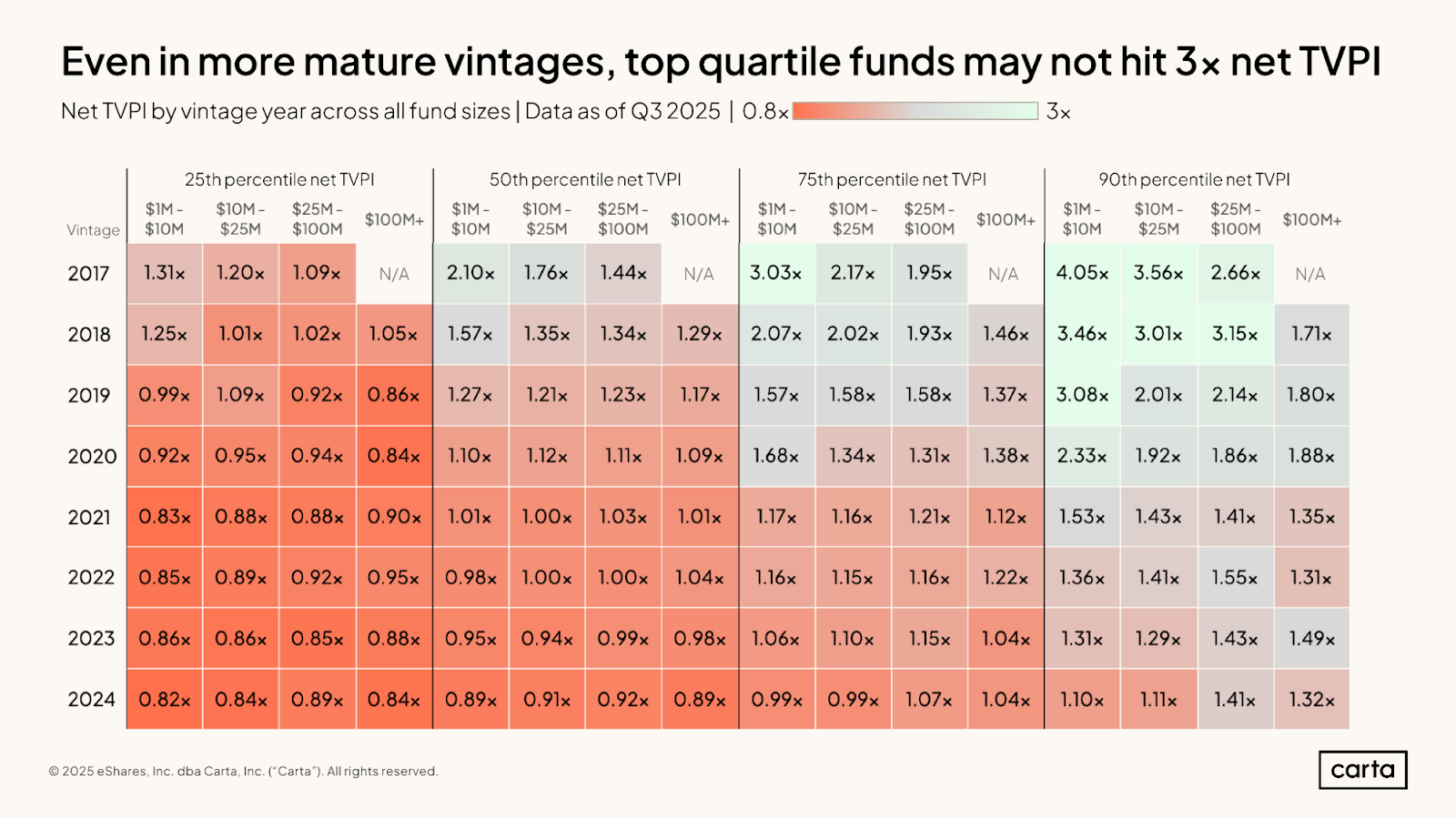

In fact, investing in venture capital has kinda fucking sucked. According to Carta, “As of the end of Q2, most VC funds across all recent vintages had a TVPI somewhere between 0.8x and 2x. But there are some areas where standout TVPIs are surfacing.” TVPI means Total Value To Paid-in Capital, or the amount of money you made for each dollar invested.

This chart may seem confusing, it tells you that for the most part, VCs have struggled to provide even money returns since 2017. A “decent” TVPI is 2.5x, and as you’ll see, things have effectively collapsed since 2021. Companies are not going public or being acquired at the same rate, meaning that investor capital is increasingly locked up, meaning that limited partners are still waiting for a payoff from the last bubble, let alone this one.

Carta would update the piece in December 2025, and things would somehow get worse. TVPI soured further, suggesting a further lack of exits across the board. The only slight improvement was the median IRR rose to 0.5% for funds from 2021 and 0.1% for funds from 2022.

In simple terms, we are looking at years of locked-up capital leaving venture capital cash-starved and a little desperate.

The worst part? All of this is happening during a generational increase in the amounts that startups need to raise thanks to the ruinous costs of generative AI, and the negative margins of AI-powered services. To quote myself:

Cursor — Anthropic’s largest customer and now its biggest competitor in the AI coding sphere — raised $2.3 billion in November after raising $900 million in June [on revenues of $83 million in, I assume, October). Perplexity, one of the most “popular” AI companies, raised $200 million in September after raising $100 million in July after seeming to fail to raise $500 million in May (I’ve not seen any proof this round closed) after raising $500 million in December 2024. Cognition raised $400 million in September after raising $300 million in March. Cohere raised $100 million in September a month after it raised $500 million.

None of these companies are profitable, nor do they have any path to an acquisition or IPO. Why? Because even the most advanced AI software company is ultimately prompting Anthropic or OpenAI’s models, meaning that their only real intellectual property is those prompts and their staff, and whatever they can build around the models they don’t control, which has been obvious from the meager “acquisitions” we’ve seen so far.

Windsurf, which was allegedly being sold to OpenAI, ended up selling its assets to Cognition in July, with Google paying $2.4 billion for its co-founders and a “licensing agreement,” similar to its acquisition of Character.Ai, where it paid $2.7 billion to rehire Noam Shazeer, license its tech, and pay off the stock of its remaining staff. This is also exactly what Microsoft did with Inflection AI and its co-founder Mustafa Suleyman.

OpenAI’s acquisitions of Statsig ($1.1bn), Io Products ($6.5bn) and Neptune ($400m) were all-stock. Every other acquisition — Wiz, Confluent, Informatica, and so on (CRN has a great list here) — is either somebody trying to pretend that (for example) Wiz is related to AI, or trying to say that a data streaming platform is AI-related because AI needs that, which may be true, but doesn’t mean that any AI startups are actually selling.

And they’re not, which is a problem, as 41% of US venture dollars in 2025 have gone into AI as of August, and according to Axios, the global number was around 51%.

A crisis is brewing. Nerdlawyer, back in October, wrote about the explosive growth of secondary markets:

Enter the secondary market—a once-niche corner of venture capital that has transformed into a primary liquidity mechanism.

What's remarkable is how quickly this market has matured. At least five major venture funds have hired full-time staff dedicated to manufacturing non-traditional exits. As Hans Swildens, CEO of Industry Ventures, explained: "All the brand name funds are all staffing and thinking through liquidity structures."

And professional buyers have flooded in. Mega-funds specializing in secondaries have raised unprecedented amounts: Lexington raised a record $23 billion fund, while HarbourVest, Ardian, and Coller Capital have raised funds in the $10-20 billion range.

In simpler terms, there are now Hot Potato Funds, where either another limited partner buys another one’s allocation, the companies themselves buy back their stock, or the stock is resold to other private investors.

And they're not alone. The secondary market is projected to handle $122 billion in assets in 2025, yet that still represents just 1.9% of total unicorn value. There's $6+ trillion in untapped liquidity potential.

The transformation of the secondary market from emergency tool to standard operating procedure represents the most significant structural shift in venture capital since the rise of unicorns. It's not a temporary fix—it's a permanent evolution driven by misaligned timeframes between fund lifecycles (10 years) and company maturation (11+ years).

For better or worse, this is the new reality of startup funding. VCs can no longer afford to simply "spray and pray" and wait for exits. They need active liquidity management strategies. And that fundamentally changes what kinds of companies get funded and how.

While this piece frames this as a positive, the reality is far grimmer. Venture capitalists are sitting on piles of immovable equity in companies worth far less than they invested at, and the answer, it appears, is to find somebody else to buy the dead weight.

According to Newcomer, only 1117 venture funds closed in 2025 (down from 2100 in 2024), and 43% of dollars raised went to the largest venture funds, per The New York Times and PitchBook, suggesting limited partners are becoming less-interested in pumping cash into the system at a time when AI startups are demanding more capital than has ever been raised.

How long can the venture capital industry keep handing out $100 million to $500 million to multiple startups a year? Because all signs suggest that the current pace of funding must continue in perpetuity, as nobody appears to have worked out that generative AI is inherently unprofitable, and thus every single company is on the Silicon Valley Welfare System until everybody gives up, or the system itself cannot sustain the pressure.

I’ve read too many people make off-handed comments about this “being like the dot com boom” and saying that “lots of startups might die but what’s left over will be good,” and I hate them for both their flippancy and ignorance.

None of the current stack of AI companies can survive on their own, meaning that the venture capital industry is holding them up. If even one of these companies falters and dies, the entire narrative will die. If that happens, it will be harder for AI companies to raise, and even harder to sell an AI company to someone else.

This is a punishment for a decade-plus of hubris, where companies were invested in without ever considering a path to profitability. Venture capital has made the same mistake again and again, believing that because Uber, or Facebook, or Airbnb, or any number of companies founded nearly twenty years ago were unprofitable (with paths to profitability in all three cases, mind), it was totally okay to keep pumping up companies that had no path to profitability, which eventually became “had no apparent business model” (see: the metaverse, web3), which eventually became “have negative margins so severe and valuations so high that we will need an IPO at a market cap higher than Netflix.”

This is Silicon Valley’s Rot Economy — the desperate, growth-at-all-costs attachment to startups where you “really like the founder,” where “the market could be huge” (who knows if it is!), where you just don’t need to worry about profitability because IPOs and exits were easy.

Venture capital also used to be easy, because we were still in the era of hypergrowth. You could be a stupid asshole that doesn’t know anything, but there were so many good deals, and the more well-known you were, the more likely you’d be brought them first, guaranteeing a bigger payout, guaranteeing more LP capital, guaranteeing more opportunities that were of a higher quality because you were a big name. It was easier to make a valuable company, easier to get funded, and easier to sell, because the goal was always “get funded, grow as large an audience as possible, or go public/get acquired.”

As a result, venture capital encouraged growth-at-all-costs thinking. In 2010, Ben Horwitz said that “the only thing worse for an entrepreneur than start-up hell (bankruptcy) is start-up purgatory”:

when you don’t go bankrupt, but you fail to build the No. 1 product in the space. You have enough money with your conservative burn rate to last for many years. You may even be cash-flow positive. However, you have zero chance of becoming a high-growth company. You have zero chance of being anything but a very small technology business (see Navisite). From the entrepreneur’s point of view, this can be worse than start-up hell since you are stuck with the small company.

This poisonous theory paid off, in that startups got used to building high-growth, low-margin companies that would easily sell to other companies or the markets themselves.

Until it didn’t, of course.

Per Nerdlawyer, IPOs have collapsed as an exit route, along with easy-to-raise capital.

Per PitchBook, since 2022, 70% of VC-backed exits were valued at less than the capital put in, with more than a third of them being startups buying other startups in 2024.

The money is drying up as the value of VCs’ assets is decreasing, at a time when VCs need more money than ever, because everybody is heavily leveraged in the single-most-expensive funding climate in history.

And as we hit this historic liquidity crisis, the two largest companies — OpenAI and Anthropic — are becoming drains on the system that, in a very real sense, are participating in a massive redistribution of capital reserved for startups to one of a few public companies.

No, really!

OpenAI is trying to raise as much as $100 billion in funding so it can continue to pass money to one of a few public companies — $38 billion to Amazon Web Services over seven years, $22.4 billion to CoreWeave over five years, and $250 billion over an indeterminate period on Microsoft Azure. If successful, OpenAI’s venture telethon will raise more money than has ever been raised in a single round, draining funds that actual startups need. Anthropic has agreed to $70 billion in compute and chip deals across Google, Amazon and Broadcom, and that’s not including the Hut8 compute deal that Google is backing.

This money will come from what remains of venture capital, private equity and hyperscaler generosity.

Yet elsewhere, even the money that goes to regular startups is ultimately being sent to hyperscalers. That AI startup that needs to keep raising $100 million in a single round isn’t sending that cash to other startups — it’s mostly going to OpenAI (Microsoft, Amazon, CoreWeave, Google), Anthropic (Google, Microsoft, Amazon), or one of the large hyperscalers for Azure, AWS or Google Cloud.

Silicon Valley didn’t birth the next big tech firm. It incubated yet another hyperscaler-level parasite, except instead of just spending money on hyperscaler services (and raising money to do so), both Anthropic and OpenAI actively drain the venture capital system as well, as they both burn billions of dollars.

By creating something that’s incredibly expensive to run, they naturally create startups more-dependent on the venture capital system, and the venture capital system has no idea what to do other than say “just grow, baby!” Both OpenAI and Anthropic’s models might be getting cheaper on a per-million-token basis, but use more tokens, increasing the cost of inference, which in turn increases the costs of startups doing business, which in turn means OpenAI, Anthropic, and all connected startups lose more money, which increases the burn on venture capital.

This is a doom-spiral, one that can only be reversed through the most magical and aggressive turnaround we will have seen in history, and it will have to happen next year, without fail.

It won’t.

So why did venture do this?

The Devil’s Deal Of Investing In AI Startups

Folks, we haven’t seen values this big in a long time. These are the biggest numbers we’ve ever seen. They’re simply tremendous. OpenAI is maybe worth $830 billion dollars, can you believe that? They lose so much money but folks we don’t worry about that, because they’re growing so fast. We love that Clammy Sam Altman — they call him “Clamuel” — tells everybody he’s giving them one billion dollars. Data centers are going to have the biggest deals we’ve ever seen, even [tchhh sound through teeth] if we have to work with Dario.

You see, right now AI startups are big, exciting news for the limited partners funding LLM firms. Things feel exciting because the value of the assets under management (AUM) are going up, which is nothing dodgy, but just how VCs value things and if they are valuing AI stocks, that is how their fees are paid. Investing early in OpenAI allows a VC — or even an asset manager like Blackstone, which invested in 2024 — to say it has a big holding and a big increase in its AUM.

We are currently in the sowing stage.

Nevertheless, AI stocks make VCs who bet on them two years ago look like geniuses on paper. You got in early on OpenAI, Anthropic, Cursor, Cognition, Perplexity or any other company that loves to burn several dollars per dollar of revenue, you have a big, beautiful number, the biggest you’ve ever seen, and your limited partners need to pay you a fee just to manage it.

Venture capital hasn’t seen valuations like this in a long time, and on paper, it feels like a lot of VCs got in on companies worth billions of dollars. On paper, Cognition is worth $10.2 billion, Perplexity $18 billion, Cursor $29.3 billion, Lovable $6.6 billion, Cohere $6.8 billion, Replit $3 billion, and Glean $7.2 billion — massive valuations for companies that all basically do products that OpenAI or Anthropic or Amazon or Google or any number of Chinese companies are already working to clone. They are all losing tons of money and have no path to profitability.

But right now the numbers are simply tremendous. I’ve heard venture capitalists tell me that there are times when they have to agree to invest with little to no information or know that they’ll lose the opportunity to another sucker investor. I’ve heard venture capitalists say they don’t have any insight into finances.

Venture capitalists would, of course, claim I’m insane, saying that the “growth is obviously there” while pointing to whatever startup has made $100 million ARR ($8.3 million in a month), all while not discussing the underlying operating expenses. The idea, I believe, is that the current spate of AI spending is only set to increase next year, and that will…somehow lead to fixing margins? Venture capitalists staunchly refuse to learn anything other than “invest in growth and then profit from growth,” even if “profiting from growth” doesn’t seem to be happening anymore.

In reality, venture capital shouldn’t have touched LLMs with a fifteen foot pole, because the margins were obviously, blatantly bad from the very beginning. We knew OpenAI would lose $5 billion in the middle of 2024. A sane venture capital climate would have fucking panicked, but instead chose to double, triple and quadruple down.

I believe that massive valuation drawdowns are a certainty. There are losses coming.

Venture capitalists, I have to ask you: what happens if OpenAI dies? Do you think that this will make investors interested in funding or acquiring other AI startups? How much longer are we going to do this? When will venture capital realize it’s setting itself up for disaster?

And what, exactly, is the plan? OpenAI and Anthropic will suck the lakes dry like an NVIDIA GPU named after Nancy Reagan. How is this meant to continue, and what will be left when it does?

The answer is simple: there won’t be money for venture capital for a while. Those AI holdings are going to be worth, at best, 50%, if they retain any value at all. Once one of these startups die, a panic will ensue, sending venture capitalists scrambling to get their holdings acquired, until there’s little or no investor interest left.

Why would LPs ever trust venture capital after this? Why would anybody? Because based on the past four years, it doesn’t appear that venture capital is actually good at investing money — it just got lucky, year after year, until there were few ideas that could sell for hundreds of millions or billions of dollars.

Venture capital believed it knew better as it turned its back on basic business fundamentals, starting with Clubhouse, crypto, the metaverse, and now generative AI.

Yet they’re far from the only fuckwits on the dickhead express.

The Upcoming Data Center Disaster

Per Bloomberg, there were at least $178.5 billion in data-center credit deals in the US in 2025, rivaling the $215.4 billion invested in US venture capital in 2024 and the $197.2 billion invested in US VC through August 7 2025, and over $100 billion more than the $60.69 billion of data center credit deals done in 2024.

I’m very worried, and I’m going to tell you why, using a company called CoreWeave that I’ve been actively warning people about since March.

CoreWeave Is Still A Time Bomb By The Way

CoreWeave is something called a “neocloud.” It’s a company that sells AI compute, and does so by renting out NVIDIA GPUs, and as I explained a few months ago, it does so by building data centers backed by endless debt:

That’s because setting up a neocloud is expensive. Even if the company in question already has data centers — as CoreWeave did with its cryptocurrency mining operation — AI requires completely new data center infrastructure to house and cool the GPUs, and those GPUs also need paying for, and then there’s the other stuff I mentioned earlier, like power, water, and the other bits of the computer (the CPU, the motherboard, the memory and storage, and the housing).

As a result, these neoclouds are forced to raise billions of dollars in debt, which they collateralize using the GPUs they already have, along with contracts from customers, which they use to buy more GPUs. CoreWeave, for example, has $25 billion in debt on estimated revenues of $5.35 billion, losing hundreds of millions of dollars a quarter.

You know who also invests in these neoclouds? NVIDIA!

NVIDIA is also one of CoreWeave’s largest customers (accounting for 15% of its revenue in 2024), and just signed a deal to buy $6.3 billion of any capacity that CoreWeave can’t otherwise sell to someone else through 2032, an extension of a $1.3 billion 2023 deal reported by the Information. It was the anchor investor ($250 million) in CoreWeave’s IPO, too.

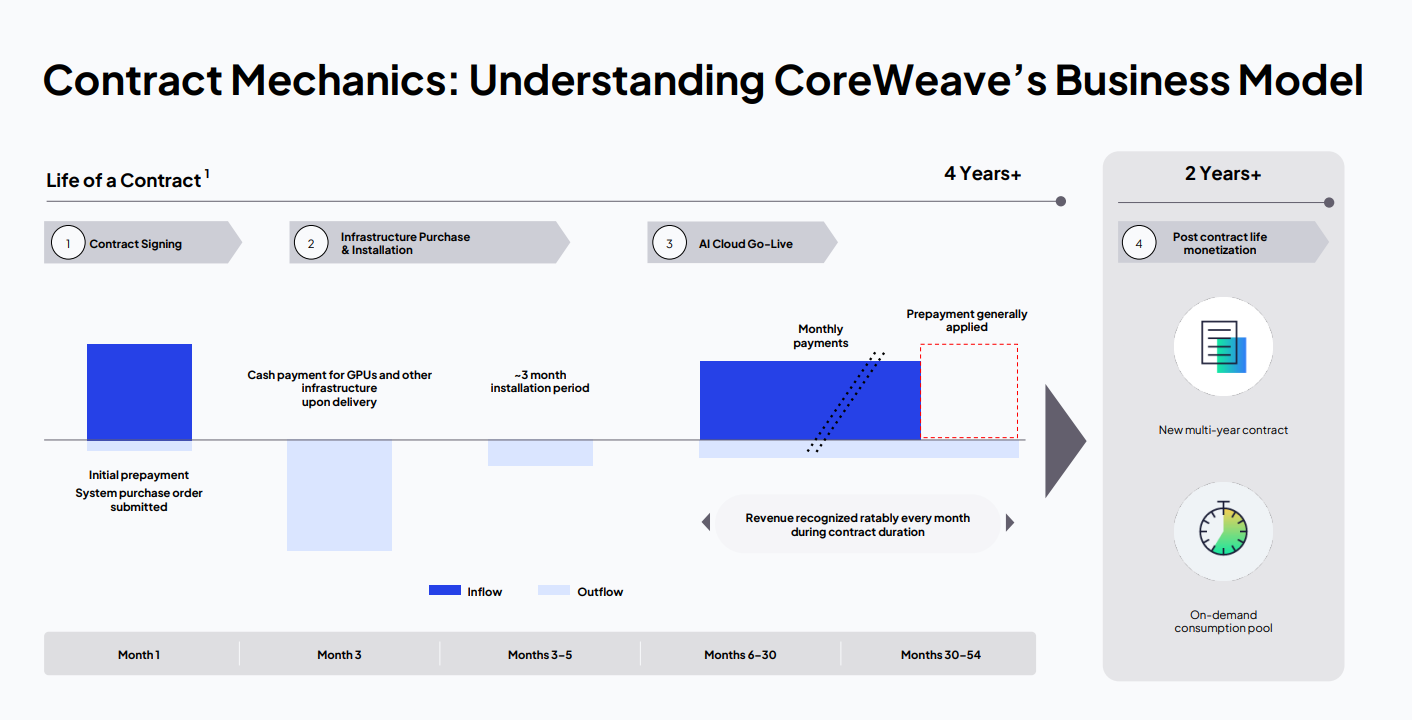

CoreWeave is one of the largest providers of AI compute in the world, and its business model is indicative of how most data center companies make money, and to explain my concerns, I’m going to explain why using this chart from CoreWeave’s Q2 2025 earnings presentation.

First, CoreWeave signs contracts — such as its $14 billion deal with Meta and $22.4 billion deal with OpenAI — before it has the physical infrastructure to service them. It then raises debt using this contract as collateral, orders the GPUs from NVIDIA, which arrive after three months, and then take another three months to install, at which point monthly client payments begin.

To really simplify this: data center developers are raising money months up to a year before they ever expect to make a penny. In fact, I can find no consistent answer to “how long a data center takes to build,” and the answer here is pretty important, because that’s how the money is gonna get made from these things.

You may notice that “monthly payments” begin at 6 to 30 months, a curious and broad blob of time. You see, data centers are extremely difficult to build, and the concept of an “AI data center” is barely a few years old, with the concept of hundreds of megawatts in one data center campus entirely made up of AI GPUs barely two years old, which means basically everybody building one is doing so for the first time, and even experienced developers are running into problems.

For example, Core Scientific, CoreWeave’s weird partner organization it tried and failed to buy, has been trying to convert its Denton Texas cryptocurrency mining data center into an AI data center since November 2024, specifically so that CoreWeave can rent it to Microsoft for OpenAI. This hasn’t gone well, with the Wall Street Journal reporting a few weeks ago that Denton has been wracked with “several months” of delays thanks to rainstorms preventing contractors from pouring concrete. The cluster is apparently going to have 260MW of capacity.

What this means for CoreWeave is that it can’t start getting paid by OpenAI, because, per its contract, customers don’t have to start paying until the compute is actually available. This is a very important detail to know for literally any data center development you’ve ever seen.

As of its latest Q3 2025 earnings filing, CoreWeave is sitting on $1.1 billion in deferred revenue (income for services not yet rendered), up from $951 million in Q2 2025 and $436 million in Q1 2025. This means deposits have been made, but the contract has yet to be serviced.

Now, I’m a curious little critter, so I went and found the 921-page $2.6 billion DDTL 3.0 loan agreement between CoreWeave and banks including Morgan Stanley, MUFG Bank and Goldman Sachs, and in doing so learned the following:

- OpenAI appears to have net 360 payment terms from CoreWeave — meaning it can pay literally a year from invoice.

- Per CoreWeave’s Q3 earnings (page 19), “...on occasion, the Company has granted payment terms up to net 360 days.”

- Per CoreWeave’s loan agreement (page 12), under “contract realization ratio,” “the sum of Projected Contracted Cash Flows applicable for the corresponding three-month period as determined on a net 360 basis.”

- CoreWeave is required to maintain something called a “contract realization ratio” of .85x — meaning that CoreWeave has to make at least 85 cents of every expected dollar or it is in default on their loan. This is important to note because it means that if, say, OpenAI decides not to pay up in a year, CoreWeave will be in real trouble.

I apologize, that suggests that CoreWeave isn’t already in trouble. Buried inside NVIDIA’s latest earnings (page 17) there was a little clue:

In the third quarter of fiscal year 2026, we entered into an agreement to guarantee a partner's facility lease obligations in the event of their default. The agreement allows our partner to secure a limited-availability facility lease backed by our credit profile, in exchange for issuing us warrants. The maximum gross exposure is $860 million, which is reduced as the partner makes payments to the lessor over five years. The partner has placed $470 million in escrow and executed an agreement to sell the data center cloud capacity, mitigating our default risk.

Credit where credit is due — eagle-eyed analyst JustDario caught this in November — but in CoreWeave’s condensed consolidated balance sheets, there sits a $477.5 million line-item under “restricted cash and cash equivalents, non-current.” Though this might not be the NVIDIA escrow — this number shifted from $617m in Q1 to $340m in Q2 — it lines up all-too-precisely…and who else would NVIDIA be guaranteeing?

In any case, CoreWeave is likely getting the best deals in data center debt outside of Oracle. It has top-tier financiers (who I will get to shortly), the full backing of NVIDIA (which is both an investor, customer and apparent financial backstop), and the ability to raise debt quickly. CoreWeave’s deals are likely indicative of how data center financing takes place, and those top-tier financiers? It’s been in basically every deal.

In fact…

Who Are The Banks Funding The Data Center Credit Boom?

So, I went and dug through a pile of 26 prominent data center loan deals, including the proposed $38 billion debt package that Oracle and Vantage Data Center Partners are raising for Stargate Shackelford and Wisconsin, Stargate Abilene, New Mexico, SoftBank’s $15 billion bridge loan (which I included for a reason that will become obvious shortly) and multiple CoreWeave loans, and found a few commonalities:

- Blue Owl was present in every single Stargate deal, other than the $38 billion package being raised by Vantage. It also was involved in a $1.3 billion Australian data center debt package by virtue of owning Stack Infrastructure. Remember that name.

- MUFG (Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group) was present in 17 out of 26 of the deals, including three separate CoreWeave financings, Stargate New Mexico ($18 billion), the $38 billion Stargate TX/WI deal for Oracle, SoftBank’s bridge loan, and a $5 billion “green loan” package for Vantage Data Centers (who are the ones building the Stargate TX/WI data centers).

- JP Morgan Chase was involved in eight deals, but they were some of the largest — CoreWeave’s October 2024 financing, DDTL 3.0 and November financing, the funding behind Stargate Abilene, the $38 billion Oracle deal, and Blue Owl’s acquisition of IPI Partners’ Data Centers in 2024. They also were part of SoftBank’s bridge loan.

- Deutsche Bank was involved in SoftBank’s bridge loan, but also three smaller deals: a $212 million data center in Seoul, CoreWeave’s 2024 debt, CoreWeave’s November financing, and a data center in Latin America. It also was part of a $610 million data center project in Virginia, as well as a €1 billion data center project in Germany (invested in with NVIDIA).

- BNP Paribas? Seven deals: CoreWeave’s DDTL 3.0, Stargate New Mexico, Stargate WI/TX, the acquisition of IPI Partners by Blue Owl, the $212m deal in Seoul, and a data center in Chile.

- Morgan Stanley? Eight, including CoreWeave’s October 2024, DDTL 3 and November loans, Stargate New Mexico, Stargate WI/TX, EQT’s EdgeConnex financing deal, and, of course, SoftBank’s bridge loan.

- SMBC (Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation)? Seven deals, all notable — CoreWeave’s DDTL 3.0 and November financing, Stargate New Mexico, Stargate TX/WI, a data center in Rowan MD (also involving MUFG, TD Securities and HSBC), as well as the data centers in Chile and Latin America. Oh, and SoftBank’s bridge loan.

I realize there are far more data center deals than these, but I wanted to show you exactly how centralized these deals are.

The largest deals — the $38 billion Stargate TX/WI deal and $18 billion Stargate New Mexico deal — both involved Goldman Sachs, BNP Paribas, SMBC and MUFG, and all four of those companies have, at some point, funded CoreWeave. In fact, everybody appears to have funded CoreWeave at some point — CitiBank, Credit Agricole, Societe Generale, Wells Fargo, Carlyle, Blackstone, BlackRock, Barclays, Magentar, and Jefferies to name a few.

Of the 40 banks and financial institutions I researched, 24 have, at some point, loaned to or organized debt for CoreWeave. Of those institutions, Blackstone, Deutsche Bank, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, MUFG and Wells Fargo have done so multiple times.

CoreWeave is a deeply unprofitable company saddled with incredible debt and deteriorating margins, with one of its largest clients paying net 360, and, as I’ve said, is arguably the best-financed data center company in the world.

What I’m getting at is that most data center deals are likely much worse than the terms that CoreWeave faces, and are likely financed in a similar way, where a client is signed for data center capacity that doesn’t exist, such as when Nebius raised $4.3 billion through a share sale and convertible notes (read: loans) to handle its $17.4 billion data center contract with Microsoft, and guess what? Goldman Sachs acted as lead underwriter on the deal, with assistance from Bank of America, CitiGroup, and Morgan Stanley, all three of which have invested in CoreWeave.

The AI Data Center Bubble Is Really, Really Bad

AI data centers are expensive, require debt due to the massive cost of construction and GPUs, and all take at least a year, if not two to start generating revenue, at which point they also begin losing money because it seems that renting out AI GPUs is really unprofitable.

Every single major bank and financial institution has piled hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars into building data centers that take forever to even start generating money, at which point they only seem to lose it. Worse still, NVIDIA sells GPUs on a one-year upgrade cycle, meaning that all of those data centers being built right now are being filled with Blackwell chips, and by the time they turn on, NVIDIA will be selling its next-generation Vera Rubin chips.

Now, you’ve probably heard that Vera Rubin will use the same racks (Oberon) as Blackwell, which is true to an extent, but won’t be true for long, as NVIDIA intends to shift to Kyber racks in 2027, hoping to build 1MW IT racks (which will involve entire racks-full of power supplies!), meaning that all of those data centers you see today — whenever they get built! — will be full of racks incompatible with the next generation of GPUs.

This will also decrease the value of the assets inside the data centers, which will in turn decrease the value of the assets held by the firms investing. Stargate Abilene? The one invested in by JP Morgan, Blue Owl, Primary Digital Infrastructure and Societe Generale? The one that’s heavily delayed and won’t be ready until the end of 2026 at earliest? Full to the brim with two-year-old GB200 racks!

By the beginning of 2027, Stargate Abilene will be obsolete, as will any and all data centers filled with Blackwell GPUs, as will any and all data centers being built today. Every single one takes 1-3 years and hundreds of millions (or billions) in debt, every single one faces the same kinds of construction delays, and better yet, almost all of them will turn on in roughly the same time frame.

Now, I ain’t no economist, but I do know that “supply and demand” has an effect on pricing. What do you believe happens to the price of renting a Blackwell GPU when all of these data centers come on? Do you think it becomes more valuable? Or less?

And while we’re on the subject, what do you think happens if there isn’t sufficient demand?

Right now, OpenAI makes up a large chunk of the global sale of compute — at least $8.67 billion of Azure revenue through September 2025, $22.4 billion of CoreWeave’s backlog, $38 billion of Amazon’s backlog, and so on and so forth — and made, based on my reporting, just over $4.5 billion in that period. It cannot afford to pay anybody, and nowhere is that more obvious than when it negotiated year-long payment terms for CoreWeave.

Otherwise, when you remove the contracts signed by hyperscalers and OpenAI (which I do not believe has paid anybody other than Microsoft yet), based on my analysis, there was less than a billion dollars of AI compute revenue in 2025, or 0.5831% of the money spent on data centers.

Hyperscaler revenue is also immediately questionable, with Microsoft’s deal with Nebius (per its 6k filing) set to default in the event that Nebius cannot provide the capacity it sold out of its unfinished Vineland, New Jersey data center, which is being built by DataOne, a company which has never built an AI data center with a CEO that has his LinkedIn location set to “United Arab Emirates” with funding from a concrete firm that is also a vendor on the construction project.

I also believe Microsoft is setting Nebius up to fail. Based on discussions with sources with direct knowledge of plans for the Vineland, New Jersey data center, Nebius has agreed to timelines that involve having 18,000 NVIDIA B200 and B300 GPUs by the end of January for a total of 50MW, with another 18,000 B300s due by the end of May. On speaking with experts in the field about how viable these plans are, two laughed, and one told me to fuck off.

If Nebius fails to build the capacity, Microsoft can walk away, much like OpenAI can walk away from Stargate in the event that Oracle fails to build it on time (as reported by The Information in April), and I believe that this is the case for literally any data center provider that’s building a data center for any signed-up tenant. This is another layer of risk to data center development that nobody bothers to discuss, because everybody loves seeing these big, beautiful numbers.

Blue Owl In A Coal Mine

Except the numbers might have become a little too beautiful for some.

A few weeks ago, the Financial Times reported that Blue Owl Capital had pulled out of the $10 billion Michigan Stargate Data Center project, citing “concerns about its rising debt and artificial intelligence spending.” To quote the FT, “Blue Owl had been in discussions with lenders and Oracle about investing in the planned 1 gigawatt data centre being built to serve OpenAI in Saline Township, Michigan.”

What debt, you ask? Well, Blue Owl — formerly the loosest legs in data center financing — was in CoreWeave’s $600 million and $750 million debt deals for its planned Virginia data center with Chirisa Technology Parks, as well as a $4 billion CoreWeave data center project in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Stargate Abilene and Stargate Mexico, Meta’s $30 billion Hyperion data center, and a $1.3 billion data center deal in Australia through Stack Infrastructure, a company it owns through its acquisition of IPI Partners.

To be clear, Blue Owl “pulling out” is not the same as a regular deal. It’s a BDC — Business Development Corporation — that invests both its own money and rallies together various banks, in this case SMBC, BNP Paribas, MUFG and Goldman Sachs (all part of Stargate New Mexico).