A series of trials have come to an end that have found that a four-day workweek would be a net positive to both workers and their productivity. The trial specifically moved workers from a 40-hour workweek to either a 35 or 36-hour workweek at the same pay grade. The way that this has been covered suggests that the study actually removed people from an entire day of the working week, which is not what it did, and indeed the narrative has quickly become around “companies shifting to a four day work week.” There has been much handwringing over the idea that businesses will have “an extra weekend day,” and the Washington Post’s Christine Emba made some points around what this extra day means:

But most said the four-day week would give them more time to do the things that make them … themselves. Some wanted to pursue a skilled pastime that would enrich their lives, such as playing an instrument or making art. Others thought they would spend the extra day with their friends and families — describing it not as drudgery or “child care,” the exhausting task that has pulled mothers especially from the workforce, but quality time. There was mention of various hobbies and associations, of going to museums, taking walks, spending time at church.

These sorts of activities are unlikely to be recognized as creating economic value. But they’re obviously rich in human value: the mastery of a craft, a connection created with others, an embeddedness in a particular community or place. These are the things that make us whole. Yet without enough free time, one can’t develop the relationships and commitments we need to truly thrive.

I agree with all of this in spirit, but there are a few critical issues that this piece and many others fall short on with regards to what this all actually means. I should add that I’m all for a four-day work week, but it shares a similarity with remote work - that it will take a chunk of society deciding to do it at once to make it actually happen. That, and the study doesn’t appear to actually be reducing itself to a four-day workweek.

The Problem With Hours

The study concerned itself specifically with a reduction in hours for workers, from 40 to 35 to 36 hours a week. Last time I checked that was not actually a full day less of work for the same pay, and the flirtation with this idea has become obsessed with the idea that you are dropping an entire day off of work.

This isn’t to say a four-day workweek is a bad idea, or that their findings aren’t substantive, or that people aren’t going to benefit from more time off. It’s that the way in which this has been framed by the media and will be framed by bosses is one that will be inherently anti-worker because the substance of the article will be ignored in favor of the idea that you will “only work four days,” similarly to how companies give “unlimited vacation time” with the hidden message of “if we approve it.”

The study was specifically framed around, and I quote, “the idea that a reduction in working hours would be an effective remedy for both Iceland’s low productivity, as

well as its poor work-life balance and wellbeing, is borne out by an array of available economic evidence.” The important difference here - and I do blame the writers of the study for even using the “four-day workweek” language to punch up the media friendliness of the study - is that this is not a study concerned with making people work Monday through Thursday or Tuesday through Friday.

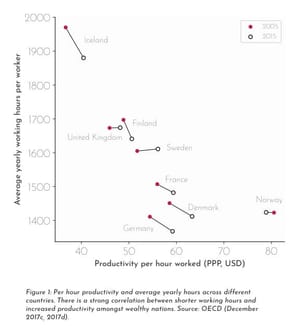

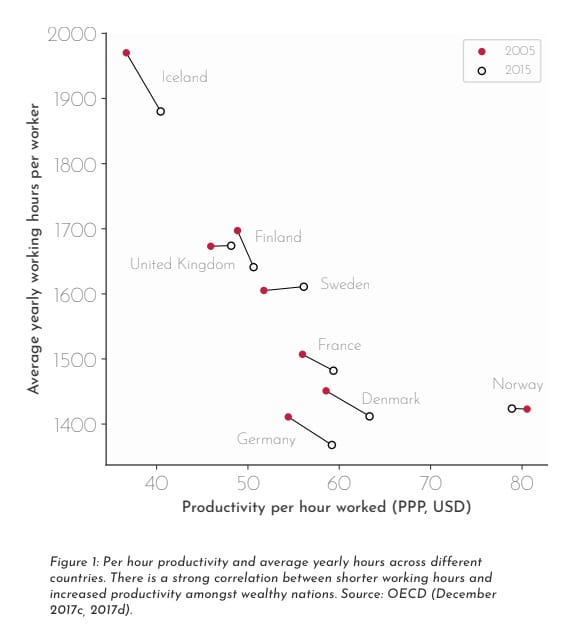

It’s a study concerned with, and in support of, reducing the hours of workers in total, and still getting the same productivity out as a result. The key differentiator here is that this means that the extra hours people were working were inefficient, rather than the overall structure of a four or five-hour workweek. It specifically included a chart that showed how more hours actually equals less productivity:

I should be clear that I think the study has interesting and valuable finds and proves a very specific thing I believe - that a productive person is not someone who works a lot of hours, but who gets a lot of work done. The problem is that this is not how this study is being viewed or analyzed, and it is not being used to justify fewer hours for the worker.

Take Kickstarter, for example, who recently garnered a ton of press based on their four-day workweek model. They are claiming that they will be "reducing their workweek from a standard 40 hours to 32 hours for the same pay and benefits,” which is admirable, and would be significantly more believable if it were coming from an anti-union company. Kickstarter’s pilot, which begins in 2022, begins with the worrying caveat that they “don’t know exactly how they’ll design this pilot yet, [but they] know that reconfiguring the way we work will involve a lot of trial and error.” Much like the rush to have hybrid offices, Kickstarter will likely take this jump based on their own internal matrix that will likely be hidden from employees, and has gotten all of this press based on saying “yeah we’re gonna do this” non-specifically.

Everything that I’ve read about this study, for the most part, focuses on the idea that people in Iceland worked fewer days a week versus fewer hours. These are not, and do not, mean the same thing, and Kickstarter’s promise of “32 hours” feels like it was accepted without any regard for what they’ve done in the past, or interrogated sufficiently.

A Business Insider piece adds that “Kickstarter will try different versions of the shortened workweek, possibly letting employees choose which extra day they have off or allowing them to just shorten their working hours across a normal five-day workweek,” but doesn’t ask the critical question of how many hours people are actually working at Kickstarter right now. I’m going to guess most people are on salary, which means that if they work more hours than their regular 8 by 5 workweek (which most salaried people do), this is going to feel fairly meaningless.

Why? Because the current state of American salary work is based on the fallacy that people work 8 hours a day 5 days a week. The nebulous laws around salary-based roles leave several categories as “exempt,” which includes a variety of “professional” job descriptions that can be used to deny basically anyone in knowledge work or above a certain pay grade overtime pay. Kickstarter is vaguely promising to reduce the hourly labor of a non-specific person, which means that other than employee dissatisfaction, there will likely be no punishment for them overreaching.

Perhaps I’m being cynical, but I can’t help but read many of these people’s promises not as a 32-hour-workweek, but as 32 hours in which you’ll be expected to get your shit done. They are also handling this in such a way that I don’t believe they’re doing the pilots with any intention other than proving that a 4-day or 32-hour workweek is untenable - that work didn’t get done, or people were unhappy and stressed. They have yet to explain (or, it seems, actually decide) what their structure will be, other than that they will do it, and they’d love to talk to the media about it vaguely, which is a critical issue because this is something that needs to be explained transparently.

Hours > Days

A lot of this discussion seems to poorly understand or discuss the actual nature of the job at hand and the current state of the salaried worker. We’ve had a few experiments of a four-day workweek recently, and the result is that there is just as much shit that needs to be done in four days as there is in five, except with the pleasure of doing it in four. My argument isn’t even that there’s too much work to do in four days - quite the opposite, in fact - but that the right way to go about this is to give workers flexible hours as long as the work gets done.

My core problem is that nothing I am reading is coming from a discussion (outside of the study) with unions or workers. It reminds me of the many stories about restaurant closures during COVID that only spoke with owners of restaurants versus workers - the narrative is firmly around generous CEOs and how well they treat their workers versus the actual effect on workers. While the Washington Post’s piece describes what will happen outside of work, few people seem to discuss the practicality of the change - how this changes work itself, how work will actually function, and so on.

We also need to figure out how a 4-day workweek can be a success for our Customer Advocacy team. As much of their work revolves around interacting with customers and resolving tickets, taking additional days off has impacted both their productivity and the volume in our customer service inboxes.

The same goes for sales, or for PR, or for any other job where the rest of the world isn’t on a 4-day workweek - you’re simply not able to do your entire job unless you’re able to be available in the weekdays that most people work.

It also fails to analyze how many hours salaried workers actually work. The nebulous idea of “full-time work” has similar issues to the idea of hybrid work - that the office is largely a place to exert power rather than do work, and hours, when you’re not paid hourly, are mostly a framework within which work is extracted from you rather than a firm expectation of labor. If a company doesn’t start paying someone the equivalent hourly pay when they switch to this model, they are looking for plausible deniability when the actual demands of the job lead into working 33, 34, or even 40 hours.

My cynicism is also rooted in the reaction that a lot of the business world has had to remote work. When I see companies freak out at the idea that people will sit at home on their computer, I cannot imagine them being respectful of their workers’ time enough to say “okay, that’s the end of the day.” If this was a true movement toward worker productivity, the people championing it (as the study does!) would be championing clear-set guidelines around productivity, execution and specifically time management, in a world where salaries are used largely to squeeze more hours out of someone with the promise of “job security.”

It would also require managers and executives to mandate and enforce hourly policies and start to pay overtime, which does not seem like a thing that will happen. They’re already terrified that they can’t stare at their workers every day.

Perhaps the reality of the 32-hour workweek is that companies are realizing that people really only work actively for 6.4 hours a day, and the rest of the time is spent dicking around online. Perhaps they’ll not consider your lunch break as part of the 32 hours, bringing you right back up to 37. Or perhaps this is a means of luring people back to the office - that you’ll only have to work 32 hours in the office, as long as you don’t mind people sneering at you when you head out the door at 3PM.

Honestly, it’ll require corporate America to start valuing contributions rather than optics, and we all know that’s not gonna happen.