Soundtrack - Radiohead - Karma Police

I just spent a week at the Consumer Electronics Show, and one word kept coming up: bullshit.

LG, a company known for making home appliances and televisions, demonstrated a robot (named “CLOiD” for some reason) that could “fold laundry” (extremely slowly, in limited circumstances, and even then it sometimes failed) or cook (by which I mean put things in an oven that opened automatically) or find your keys (in a video demo), one that it has no intention of releasing. The media generally gave it an easy go, with one reporter suggesting that a barely-functioning tech demo somehow “marked a turning point” because LG was now “entering the robotics space” with a product it had no intention of selling.

So, why did LG demo the robot? To con the media and investors, of course! Hundreds of other companies demoed other robots you couldn’t buy, and despite what reports might say, we were not shown “the future of robotics” in any meaningful sense. We got to see what happens when companies run out of ideas and can only copy each other. CES 2026 was the “year of robotics” in the same way that somebody is a sailor because they wore a captain’s hat while sitting in a cardboard box.

Yet the robotics companies were surprisingly ethical compared to the nonsensical tide of LLM-driven wank, from no-name dregs in the basement of the Venetian Expo Center to companies like Lenovo warbling about its “AI super agent.” In fact, fuck it, let’s talk about that.

“AI is evolving and getting new capabilities, sensing our three-dimensional world, understanding how things move and connect,” said Lenovo CEO Yang Yuanqing, leading into a demo of Lenovo Qira, before claiming it “redefines what it means to have technology built around you.” One would think the demo that follows would be an incredible demonstration of futuristic technology. Instead, a spokesperson walked up, asked Qira to show what it could see (IE: multimodal capabilities available for years in many models), received a summary of notifications (available in effectively any LLM integration, and incredibly prone to hallucinations), and asked “what to get her kids when she had some free time,” at which point Qira told her, and I quote, that “the Las Vegas Fashion Mall has some Labubus that children will go crazy for,” referring to the kind of tool-based web search that’s been available since 2024.

The presenter noted that Qira also can add reminders — something that has been available for years on most iOS or Android devices — and search for documents, then showed a proof-of-concept wearable that can record and transcribe meetings, a product that I saw no less than seven times during my time at CES.

Lenovo rented out the entirety of the Las Vegas Sphere to do a demonstration of a fucking chatbot powered by OpenAI’s models on Microsoft Azure, and everybody acted like it was something new. No, Qira is not a “big bet” on AI — it’s a fucking chatbot forced on anybody buying a Lenovo PC, full of features like “summarize this” or “transcribe this” or “tell me what’s on my calendar,” features peddled by business idiots that have little experience with any real-world applications of just about anything, marketed with the knowledge that the media will do the hard work of explaining why anybody should give a shit.

Want better-looking video or audio from your TV? Get fucked! You’re getting nano banana image generation from Google and other LLM features from Samsung

You can now generate images on your TV using Google’s Nano Banana model — a useless idea peddled by a company that doesn’t know what consumers actually want, varnished as making your TV-based assistant “more helpful and more visually engaging.” As David Katzmaier correctly said, nobody asked for LLMs in their TVs, allowing you to “click to search” something that’s on your TV, something that no normal person will do.

In fact, most of the show felt like companies doing madlibs with startup decks to try and trick people into thinking they’d done anything other than staple a frontend on top of a Large Language Model. Nowhere was that more obvious than the glut of useless AI-powered “smart” glasses, all of which claim to do translation, or dictation, or run “apps” using clunky, ugly and hard-to-use interfaces, all using the same LLMs, all doing effectively the same thing. These products only exist because Meta decided to blow several billion dollars on launching “AI glasses,” with the slew of copycats phrased as being “part of a new category” rather than “a bunch of companies making a bunch of useless bullshit nobody wants or needs.”

These are not the actions of companies that truly fear missing the mark, let alone the judgment of the media, analysts or investors. These are the actions of a tech industry that has escaped any meaningful criticism — let alone regulation! — of their core businesses or new products under the auspices of “giving them a chance” or “being open to new ideas,” and those ideas are always whatever the tech industry just said, even if it’s nonsensical.

When Facebook announced it was changing its name to Meta as a means of pursuing “the successor to the mobile internet,” it didn’t really provide any proof beyond a series of extremely shitty VR apps, but not to worry, Casey Newton of Platformer was there to tell us that Facebook was going to “strive to build a maximalist, interconnected set of experiences straight out of sci-fi — a world known as the metaverse,” adding that the metaverse was “having a moment.” Similarly, Futurum Group’s Dan Newman said in April 2022 that “the metaverse was coming” and that it “would likely continue to be one of the biggest trends for years to come.”

Three years and $70 billion later, the metaverse is dead, and everybody acts as if it didn’t happen. Whoops! In a sane society, investors, analysts and the media would never trust a single word out of Mark Zuckerberg’s mouth ever again. Instead, the media gleefully covered his mid-2025 “Personal Superintelligence” blog where he promised everybody would have a “personal superintelligence” to “help you achieve your goals.” Do LLMs do that? No. Can they ever do that? No. Doesn’t matter! This is the tech industry. There is no punishment, no consequence, no critique, no cynicism, and no comeuppance — only celebration and consideration, only growth.

All the while, the largest tech firms have continued growing, always finding new ways (largely through aggressive monopolies and massive sales teams) to make Number Go Up to the point that the media, analysts and investors have stopped asking any challenging questions, and naturally assumed that they — and the financiers that back them — would never do something really stupid. The tech, business and finance media had been well-trained at this point to understand that progress was always the story, and that failure was somehow “necessary for innovation,” whether or not anything was innovative.

Over time, this created an evolutionary problem. The successes of companies like Uber — which grew to quasi-profitability after more than a decade of burning billions of dollars — convinced journalists that startups had to burn tons of money to grow. All that it took to convince some members of the media that something was a good idea was $50 million or more in funding, with larger funding rounds making it — for whatever reason — less palatable to critique a company, for fear that you would “bet against a winner,” as the assumption would be that this company would go public or get acquired, and nobody wants to be wrong, do they?

This naturally created a world of startup investment and innovation that oriented itself around the growth-at-all-costs nightmare of The Rot Economy. Startups were rewarded not for creating real businesses, or having good ideas, or even creating new categories, but for their ability to play “brainwash a venture capitalist,” either through being “a founder to bet on” or appealing to the next bazillion-dollar TAM boondoggle. Perhaps they’d find some sort of product-market fit, or grow a large audience by providing a service at an unsustainable cost, but this was all done with the knowledge of an upcoming bailout via IPO or acquisition.

The Stagnation of Venture Capital

Over the years, venture capital was rewarded for funding “big ideas” and that, for the most part, paid off. Eventually those “big ideas” stopped being “big ideas for necessary companies” and became “big ideas for growing as fast as possible and dumping onto the public markets or other companies afraid that they’d be left behind.”

Taking a company public used to be easy[ From 2015-2019, there were over 100 IPOs annually, with a consistent flow of M&A giving startups somewhere to sell themselves, leading up to the egregious excess of the frothy M&A and IPO market of 2021 (a year that also saw $643 billion in venture capital investment), which led to 311 IPOs that shed 60% of their value by October 2023. Years of stupid bets based on the assumption that the markets or big tech would buy any company that remotely scared them piled up.

This created the current liquidity crisis in venture capital, where funds raised after 2018 have struggled to return any investor money, making investing in venture capital firms less lucrative, which in turn made raising money from Limited Partners harder, which in turn led to less money being available for startups that were now paying higher rates as SaaS companies — some of whom were startups — gouged their customers with higher rates every year.

Every single one of these problems comes down to one simple thing: growth. Limited Partners invest in venture capitalists that can show growth, and venture capital invested in companies that would show growth, which would in turn increase their value, which would allow them to sell for a greater amount of money. The media covers companies based not on what they do but their potential value, a value that’s largely dictated by the vibes of the company and the amount of money that they’ve raised from investors.

And all of that only makes sense if there’s liquidity, and based on the overall TVPI (the amount of money you made for each dollar invested) of funds raised after 2018, the majority of VC firms have not been able to actually make their investors more than even money in years.

Why? Because they invested in bullshit. It’s that simple. The companies they invested in are dogs that will never go public or sell to another company. While many people believe that venture capital is about making early, risky bets on vestigial companies, the truth is that the majority of venture dollars go into late-stage bets. A kinder person would frame this as “doubling down on established companies,” but those of us living in reality see it for what it is — a culture that has more in common with investing in penny stocks than it does in understanding any business fundamentals.

Perhaps I’m a little bit naive, but my perception of venture capital was that it was about discovering nascent technologies and giving them the means to make their ideas a reality. The risk was that these companies were early and thus might die, but those that didn’t die would soar. Instead, Silicon Valley waits for angel and seed investors to take the risk first, reads TechCrunch, watches the (Well Well Well, If It Isn’t The) Technology Brothers, or browses Twitter all day and discovers the next thing to pile into.

The problem with a system like this is that it naturally rewards grifting, and it was inevitable that a kind of technology would come along that worked against a system that had chased out any good sense or independent thought.

Generative AI lowers the barrier of entry for anybody to cobble together a startup that can say all the right things to a venture capitalist. Vibe coding can create a “working prototype” of a product that can’t scale (but can raise money!), the nebulous problems of LLMs — their voracious need for data, the massive data security issues, and so on — offer founders the chance to create slews of nebulous “observability” and “data veracity” companies, and the burdensome cost of running anything LLM-adjacent means that venture capitalists can make huge bets on companies with inflated valuations, allowing them to raise the Net Asset Value of their holdings arbitrarily as other desperate investors pile into later rounds.

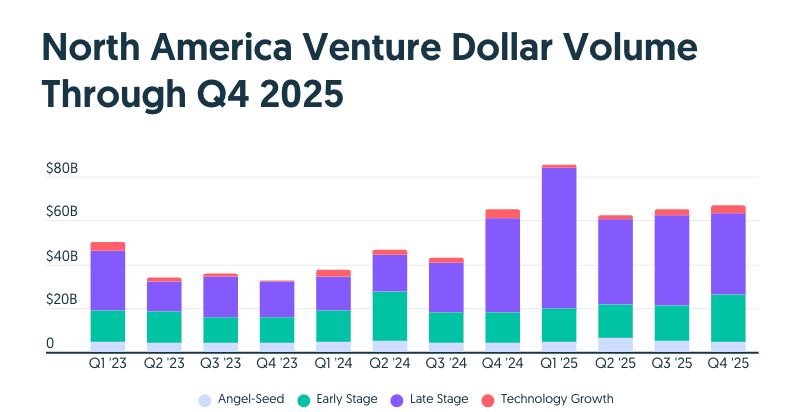

As a result, AI startups took up 65% of all venture capital funding in Q4 2025. Venture capital’s fundamental disconnection from value-creation (or reality) has led to hundreds of billions of dollars flowing into AI startups that have already-negative margins that get worse as their customer base grows and the cost of inference (creating outputs) is increasing, and at this point it’s obvious that it is impossible to create a foundation lab or LLM-powered service that makes a profit, on top of the fact that it appears that renting the GPUs for AI services is also unprofitable.

I also need to be clear that this is far, far worse than the dot com bubble.

US venture capital invested $11.49 billion ($23.08bn in today’s money) in 1997, $14.27 billion ($28.21 billion in today’s money) in 1998, $48.3 billion ($95.50 billion in today’s money) in 1999, and over $100 billion ($197.71 billion) in 2000 for a grand total of $344.49 billion (in today’s money) — a mere $6.174 billion more than the $338.3 billion raised in 2025 alone, with somewhere between 40% and 50% of that (around $168 billion) going into AI investments, and in 2024, North American AI startups raised around $106 billion.

According to the New York Times, “48 percent of dot-com companies founded since 1996 were still around in late 2004, more than four years after the Nasdaq’s peak in March 2000.” The ones that folded were predominantly dodgy and nakedly unsustainable eCommerce shops like WebVan ($393m in venture capital), Pets.com ($15m) and Kozmo ($233m), all of which filed to go public, though Kozmo failed to dump itself onto the markets in time.

Yet in a very real sense, the “dot com bubble” that everybody experienced had very little to do with actual technology. Investors in the public markets rushed with their eyes closed and their wallets out to invest in any company that even smelled like the computer, leading to basically any major tech or telecommunications stock trading at a ridiculous multiple of their earnings per share (60x in Microsoft’s case).

The bubble burst when the bullshit dot-com stocks died on their ass and the world realized that the magic of the internet was not a panacea that would fix every business model, and there was no magic moment where a company like WebVan or Pets.com would turn a horribly-unprofitable business into a real one. Similarly, companies like Lucent Technologies stopped being rewarded for doing dodgy, circular deals with companies like Winstar, leading to the collapse of the telecommunications bubble that led to millions of miles of dark fiber being sold dirt cheap in 2002. The oversupply of dark fiber was eventually seen as a positive, leading to an eventual surge in demand as billions of people came online toward the end of the 2000s.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Ed, isn’t that exactly what’s happening here? We’ve got overvalued startups, we’ve got multiple unprofitable, unsustainable AI companies promising to IPO, we’ve got overvalued tech stocks, and we’ve got one of the largest infrastructural buildouts of all time. Tech companies are trading at ridiculous multiples of their earnings-per-share, but the multiples aren’t as high. That’s good, right?

No. No it isn’t. AI boosters and well-wishers are obsessed with making this comparison because saying “things worked out after the dot com bubble” allows them to rationalize doing stupid, destructive and reckless things.

Even if this was just like the dot com bubble, things would be absolutely fucking catastrophic — the NASDAQ dropped 78% from its peak in March 2000 — but due to the incredible ignorance of both the private and public power brokers of the tech industry, I expect consequences that range from calamitous to catastrophic, dependent almost entirely on how long the bubble takes to burst, and how willing the SEC is to greenlight an IPO.

The AI bubble bursting will be worse, because the investments are larger, the contagion is wider, and the underlying asset — GPUs — are entirely different in their costs, utility and basic value than dark fiber. Furthermore, the basic unit economics of AI — both in its infrastructure and the AI companies themselves — are magnitudes more horrifying than anything we saw in the dot com bubble.

In simpler terms, I’m really fucking worried, and I’m sick and tired of hearing people making this comparison.